Name

Ho’e-oesta-oo-nah’e

Prayer Cloth Woman

Tribal Nation

Tsetsehestahese

The People Alike

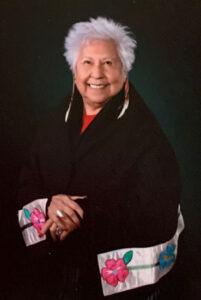

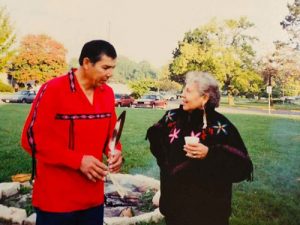

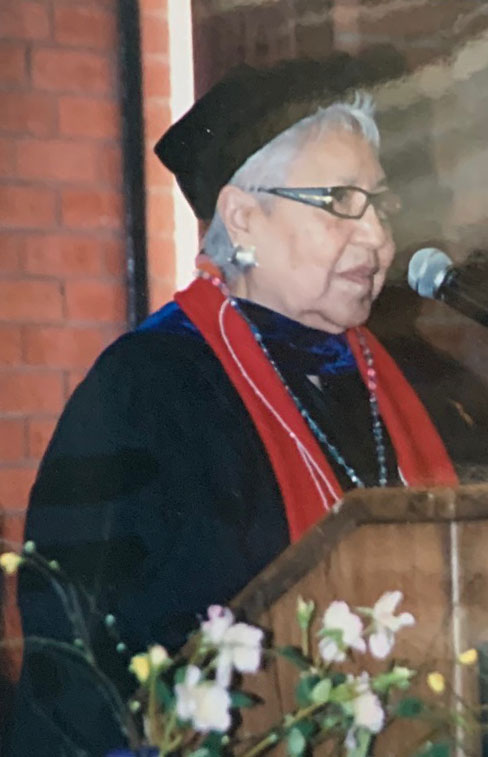

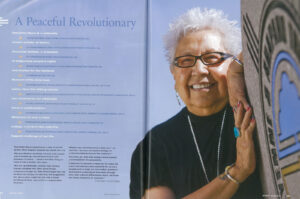

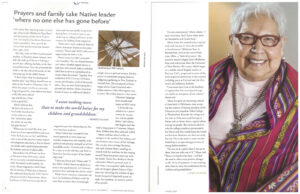

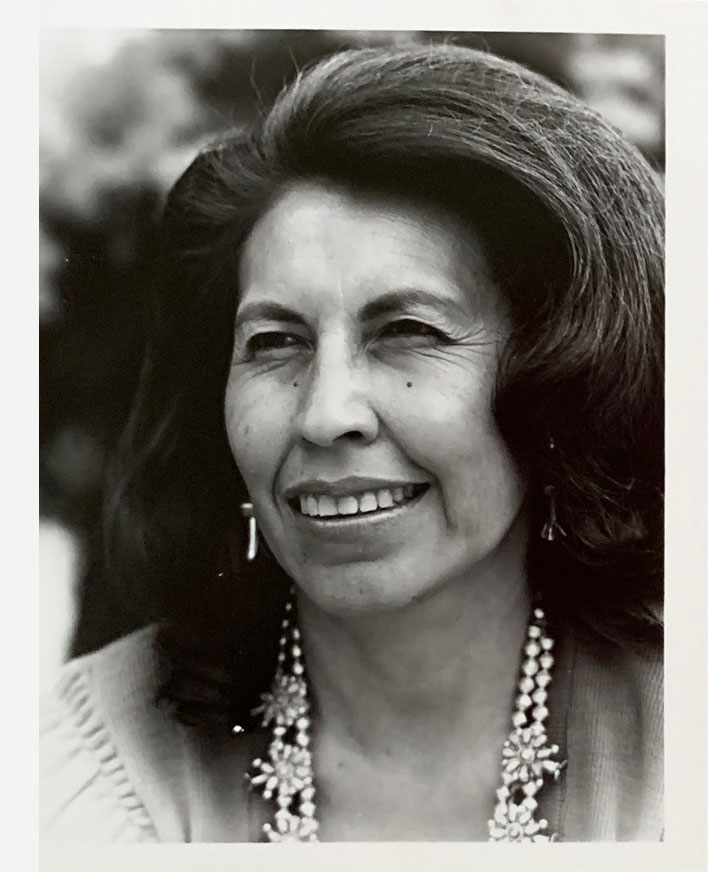

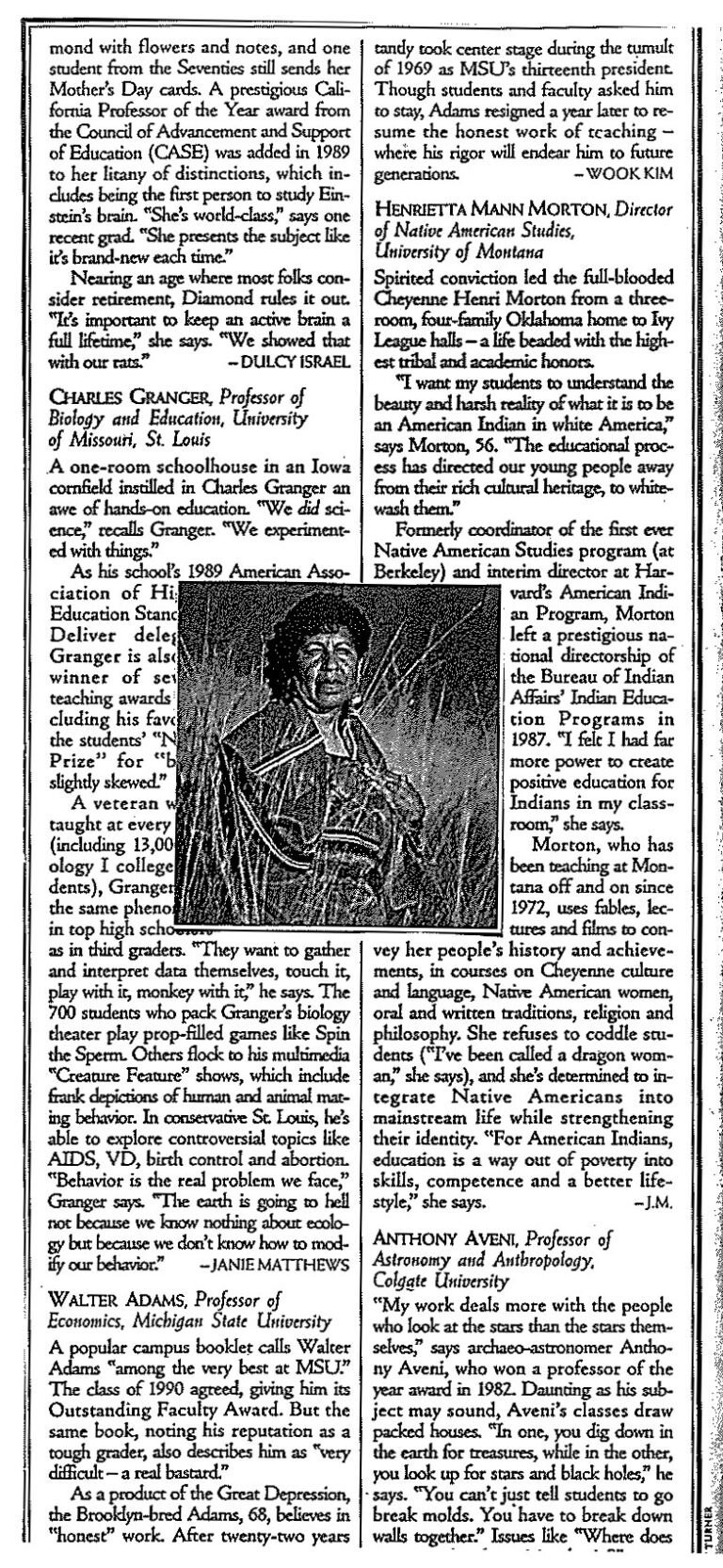

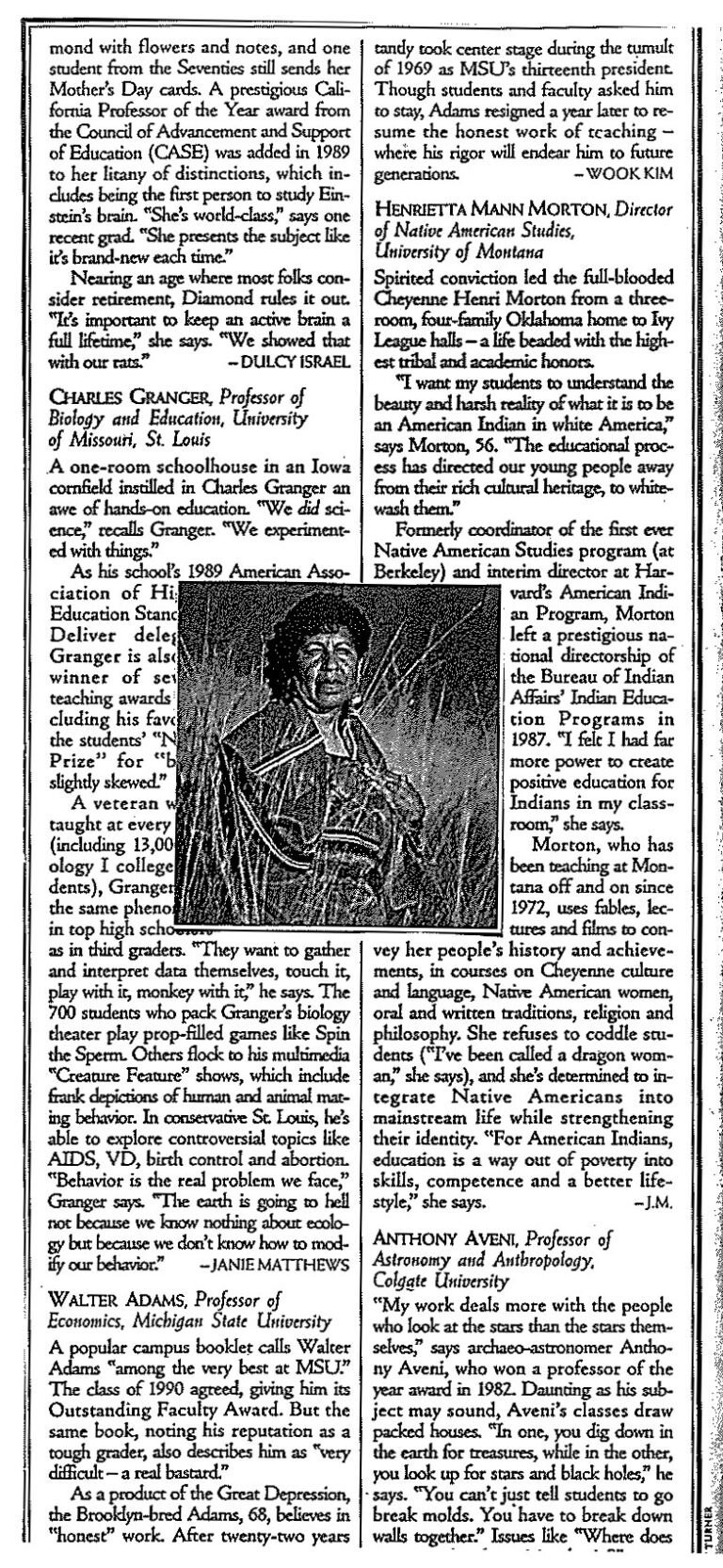

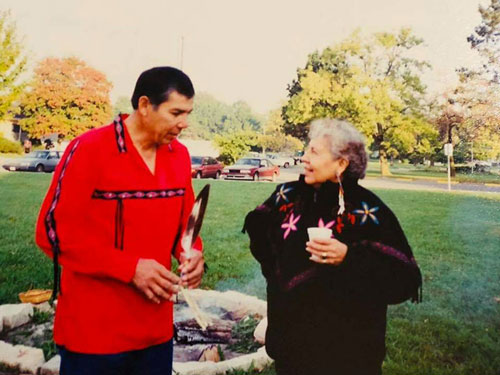

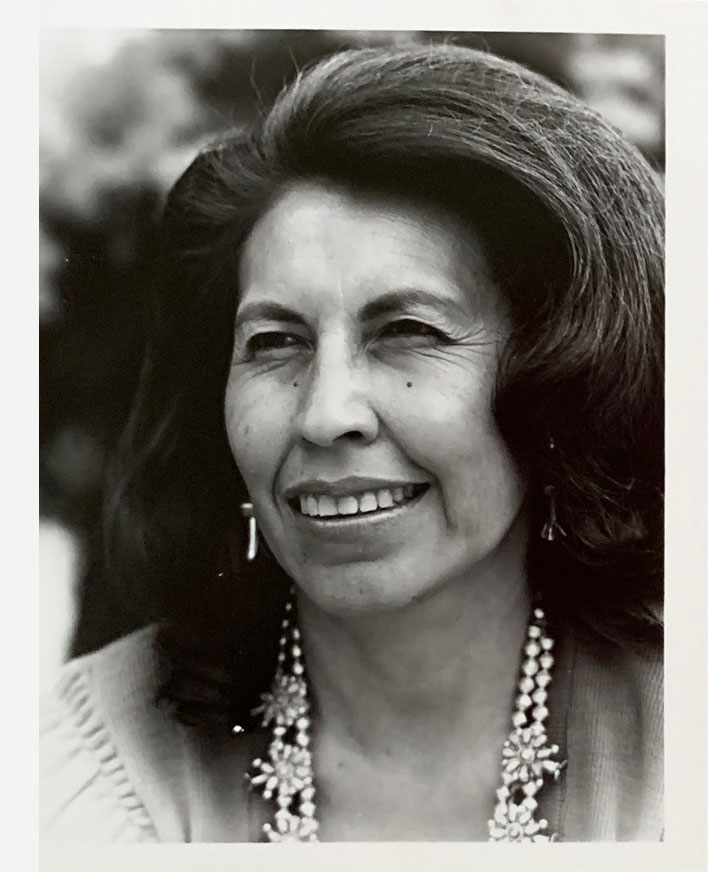

Dr. Henrietta Mann, (Southern Cheyenne), has brilliantly and energetically bridged Western educational settings with traditional, spiritual ways of being. She extends the roots of who she is and where she comes from no matter where she is in the world, creating a loving and encouraging space of strength for people around her. Henri points out, in her reflection on elders’ Spirit Aligned Leadership: “we still possess our abilities to lead, to love humankind, to yet carry out our peoples’ wealth of traditional knowledge, to have a respect for all life, to maintain a compassionate view of the world, and to be concerned about the desecration of Mother Earth, all of which did not stop at the door to the spare bedroom or forgotten wings of the assisted care facility.” Dr. Henri relates to White Buffalo Woman and is strong in Sun Dance—she served as the spiritual compass during the formation of NMAI, as she did as a professor in Montana and centering work in the academy, in government, in tribal affairs. She views her legacy as a giveaway to the next generation.

MORE INFORMATION

Audio/Video

Henrietta Mann Interview

If these two women had not survived, and had the brave hearts that they do, I might not have been here.

Dr. Henrietta Mann relates Cheyenne history through her family, including her two great grandmothers who survived the massacres at Sand Creek and along the Washita River. Through this intimate telling of history, we gain an understanding of lived experiences that created the strong woman that Henrietta is. Dr. Mann describes the “four stops in life” that we make and reflects on her personal experiences through these stages and where she is now as an elder.

Video

Gallery

Homeland Images

Winter Count

Winter Count

Winter counts are pictorial calendars or histories in which tribal records and events were recorded by Native Americans in North America.

1934

May 22

Henrietta Mann Was Born

Twenty Stands Woman/Standing Twenty Woman Henrietta Mann was born at 4:47am, May 22, 1934 at the Clinton Indian Hospital, Custer County, Oklahoma, the daughter of Holy Bird Henry Mann and Day Woman Lenora Wolftongue Mann, each 4/4 Cheyenne.

Paternal Grandparents: Spotted Horse Fred Mann and The Woman Who Comes to Offer Prayer/Prayer Woman/Prayer Cloth Woman Lucy Whitebear Mann

Maternal Grandparents: Deer Elmer Wolftongue and Bertha Powder Face Wolftongue

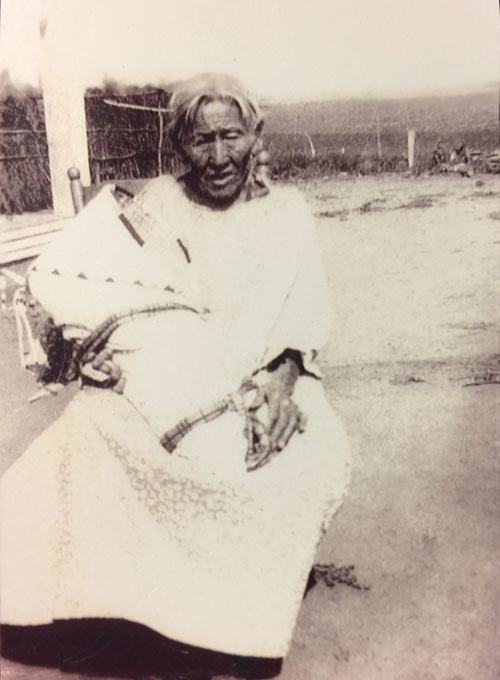

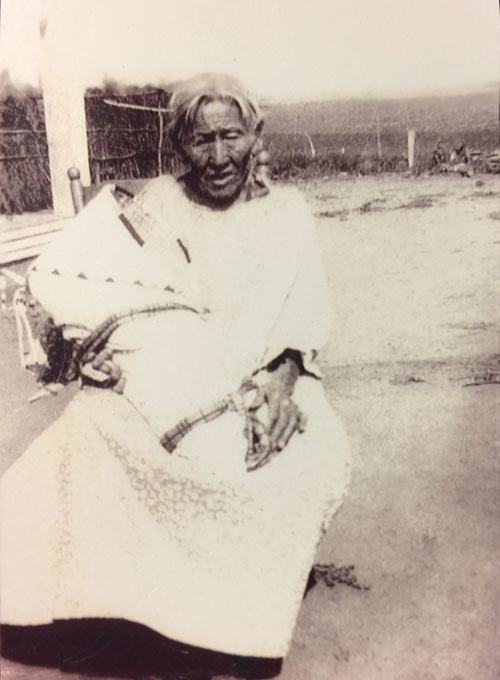

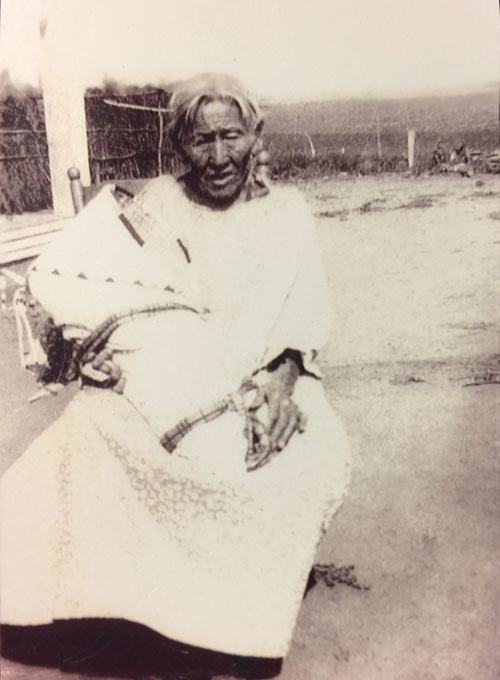

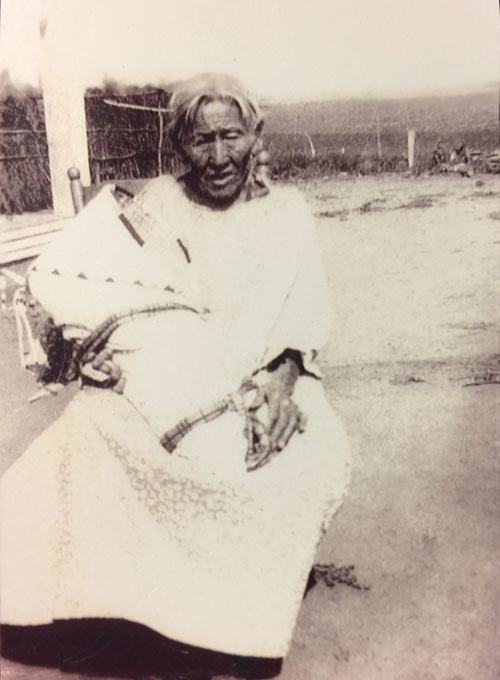

Paternal Great-Grandmother: Homa’oestaa’e/Homae’voestaa’e White Buffalo Woman was a Sand Creek and Washita Survivor. She is often referred to just as Voestaa’e, which translates as White Buffalo Calf Woman.

On the first morning following the coming home of mother and child, White Buffalo Woman blessed the infant Henrietta in the old way. She held her body as one holds a pipe, and pointed her headfirst to each of the four sacred directions of the universe (SE, SW, NW, NE), up, then laid her gently upon the earth supported by her hands. She was wrapped in a softly tanned calf hide, which was her primary blanket. Afterward, she prayed for the baby, and for all those assembled, who had come to welcome the infant to life on earth and to witness this special ceremony.

Henrietta selected Chairman of Christmas Celebration

As an infant of less than one year of age, Henrietta was selected by the Hammon Whiteshield Camp Christmas Committee to be the Chairman of their annual Christmas Celebration. As she was still but a baby, her parents, grandfather, and great-grandmother assumed this role on her behalf and carried out the celebration. It was looked upon a community honor and, essentially, became Henrietta’s first servant leadership role.

1938

White Buffalo Woman walked away from this Earth

White Buffalo Woman walked away from this earth to go to live in that eternal camp in the stars. She lies at rest in the Hammon Indian Mennonite Cemetery, Hammon, OK far from the place she was born in what is believed to be Wyoming Territory in 1853. She was among the last of the Cheyenne to make the break from the Buffalo and Horse Culture to life on the Southern Plains.

But two generations removed from Cheyenne Horse Culture, the Mann family still kept a herd of horses. A beautiful black and white paint was born and given to Henrietta, whom she named Ginger. Until the day they walked away from earth, the two men were always proud to proclaim that Henrietta had broken the pony herself, as was oftentimes the case for Cheyenne women.

Henrietta grew up primarily in a Cheyenne speaking environment, and even after she was enrolled in public school, one of her aunts Ruth Sooktis-Mann Big Left Hand moved in with the family. Ruth became her private Cheyenne language teacher every evening after she came home from school. Dinner conversation was in Cheyenne, but afterward, the language became bilingual, acknowledging the fact that she had to also improve her English speaking skills.

1950s

Selected to be part of Cheyenne dance group

Early in the 1950s during summer breaks, Henrietta was among those selected to be a part of the Cheyenne dance group who participated in dance exhibitions at the Gallup Intertribal Ceremonial, Gallup, NM for which Albert Hoffman was the Director. She was also selected as a member of the dance group which danced at Fourth of July gatherings in Flagstaff, AZ for which David Fan Man was the Director.

1951

Graduated from Hammon High School

Graduated from Hammon High School, Hammon, Oklahoma as the Salutatorian of her graduating class.

Upon high school graduation, Henrietta’s parents and grandfather put up a Native American Church, peyote meeting for her, the last time they did so. Her mother brought in the morning water. They did so to give thanks for her having acquired a high school diploma and to ask for continued guidance in her pursuit of higher education, as she was going on to college that summer.

Many years later in 1982 after she had completed her Doctor of Philosophy degree, Joe Antelope and her father, who had both attended her high school graduation peyote meeting were discussing the completion of her university education and agreed that Ma’heo’o, the Cheyenne “Great One” had heard their prayers.

Mr. Antelope had been the Fireman at that 1951 peyote meeting, and he later became the Keeper of the Cheyenne Sacred Arrows, the highest spiritual authority among the Cheyenne.

1954

Graduated from Southwestern State College

Graduated from Southwestern State College, Weatherford, Oklahoma with a Bachelor of Arts Degree in Education with a major in English (July 29).

In acknowledgment of this educational achievement, the family changed her Cheyenne name to that of her paternal grandmother, Ho’e-osta-oo-nah’e, which translates into English as The Woman Who Comes to Offer Prayer/Prayer Woman/Prayer Cloth Woman.

1955

April 21

Mark Alan Thompson born

Mark Alan Thompson, son born April 21, 1956, from Henrietta’s first marriage to George Lewis Thompson. Mark died September 12, 1990, from renal failure and hypotension exacerbated by chronic alcoholism. It is the most heartbreaking experience to lose a child.

1959

Married Alfred Whiteman, Jr.

Married Alfred Whiteman, Jr. (Cheyenne-Arapaho) Commercial Artist/Indian Artist. Born in Colony, Oklahoma, his mother was Nellie Rouse also known as Emily Washee (Cheyenne); his father Alfred Sr. was the grandson of Southern Arapaho Chief Little Raven, who signed the 1861 Treaty of Fort Wise, the 1865 Treaty of the Little Arkansas, and the 1867 Treaty of Medicine Lodge.

Chief Little Raven’s daughter Anna attended Carlisle Indian Industrial Training School in Carlisle, PA. Upon her return home, she married White Shirt (Arapaho). Two of their children Stephen and Ruth were listed on the Cheyenne and Arapaho Tribal Rolls as White Shirt; however, their youngest son Alfred was listed on the Tribal Rolls with the last name of Whiteman. Technically he should have been Alfred Whiteshirt.

1960

October 25

Alden Alfred Whiteman was born

I had grown up as virtually an only child and did not have a younger brother until I was eleven years old. His name was Ame’haohtse Flying Man Henry Mann, Jr. and I loved, will always love, this one sibling of mine, who died in 1979. I treated him like a living doll and cared for him as an older “sister mama” does. He used to call me “Mama.”

It was not until I was an adult that I learned that my parents had invoked a seldom-used Cheyenne tradition and made a vow to not have another child for ten years. Few parents made such a vow, which if broken would result in the death of the child. Such a sacrifice was made to give the child the best upbringing possible and to provide a strong cultural foundation. I finally understood why I never had siblings, although I had always wanted them.

My first magnificent love was my great-grandmother White Buffalo Woman. My first best friend was my grandfather Fred Mann, who made his home with us.

My father’s three sisters lived with us until the oldest aunt Mariam married. She was named for her aunt in English and Cheyenne. She was also Crooked Nose Woman. The other two, Rubie, Flying Woman, and Lucille, Night Walking Woman went off to Chilocco Indian School in Arkansas City, KS.

My grandfather had attended Chilocco for a while. He and his friend Amos White Hawk just showed up at the Chilocco school gates one day. They informed the administrator that they wanted to go to school, but would leave when they decided.

At that time, the federal government required three years of consecutive mandatory attendance at Off-Reservation Boarding Schools.

Because I grew up virtually an only child, I wanted to have a large family. Thus, Al and I had three children:

October 25, 1960:

Alden Alfred Whiteman

Vaoseva = Deer; Nanose’hame = Mountain Lion

January 4, 1962:

Montoya Ann Whiteman

Ma’ohkeena’e = Red Feather/Tassel Woman

November 20, 1963

Jackie Ladean Whiteman

Ame’ha’e = Flying Woman

1962

January 4

Montoya Ann Whiteman born

January 4, 1962:

Montoya Ann Whiteman

Ma’ohkeena’e = Red Feather/Tassel Woman

The family moved from Oklahoma City to Stillwater, OK

The family moved from Oklahoma City to Stillwater, OK when Al got a job as a commercial artist in the Public Information at Oklahoma State University (OSU).

By this time my aunt June Wolftongue, my mother’s sister, was living with us. She helped me with my children, and we gave Montoya her “grandmother” June’s Cheyenne name Red Feather.

1963

November 20

Jackie Ladean Whiteman born

November 20, 1963

Jackie Ladean Whiteman

Ame’ha’e = Flying Woman

Enrolled in graduate school at OSU

Since I have a great love for education, my late husband and I decided that I should pursue work toward a Master’s Degree. I consequently enrolled in graduate school in the English Department at OSU on January 23, 1963.

By the end of that year, we had seven family members, and we were one big, happy family. We also realized the cost of providing for a large family, and I went to work as the secretary in the Department of Art at OSU, and attended graduate school part-time. I stayed in the Art Department until I completed my Master’s Degree in English, and left to assume a university position at Cal Berkeley in early 1970.

In the intervening years, I juggled work and family. We also spend much time vacationing and driving to western Oklahoma to visit family and to attend dances, pow wows, meetings, and ceremonies. The children loved spending time with family, especially their “cousins.” It was their time for cultural grounding, and the beauty was they all got to know my grandfather Spotted Horse Fred Mann.

1966-1967

Elected representative of the Cheyenne & Arapaho Business Committee

I was elected the Hammon District Representative to the 15th Council of the Cheyenne & Arapaho Business Committee, headquartered at Concho, Oklahoma for a two-year term. I became the first woman ever elected to represent the Hammon Cheyenne District on the Tribes’ Business Committee.

My late husband Alfred Whiteman, Jr. also was elected as the El Reno District Representative that term. We became the first husband and wife team to ever serve in this capacity to this day.

Lawrence Hart, former jet pilot, who was the Chairman of the Business Committee, appointed me as the Chair for the Cheyenne and Arapaho Scholarship Committee. It had its own budget and operated autonomously from the Business Committee.

When we as a Business Committee finally settled our land claims with the U.S. government, we created a $500,000 trust fund for education, established a minors’ trust fund, and distributed per capita payments of $2,325.00 to all adult tribal members. I testified before the United States House of Representative on the educational trust fund, and Chief Ben Whiteshield of my district, happily announced that I was going to “Washingdyne.”

1969-1970

Became President of the Advisory School Board to the Dept. of the Interior

In keeping with the federal policy shift to Indian Self-determination, school boards were created for BIA schools, which included the one at Concho. I subsequently became the President of the Advisory School Board to the Department of the Interior, Bureau of Indian Affairs, Concho School, Concho, Oklahoma. The Concho (Manual Labor) School was located on the former Cheyenne and Arapaho Reservation.

1970

Employed as Coordinator of Native American Studies at University of Berkeley

Employed as Lecturer/Assistant Coordinator, then Coordinator, Native American Studies, Department of Ethnic Studies, University of California, Berkeley (March 1970 -June 1972). Native American Studies was new to the college/university campuses of this nation and was in the initial stages of being integrated into college/university curricula.

I arrived in Berkeley after 78 Bay Area Native Americans had moved on to Alcatraz Island in the San Francisco Bay, 1.25 miles from San Francisco. While there, they issued a “Proclamation to the Great White Father and All His People,” stating they re-claimed the island by right of discovery and offered a treaty of perpetuity, “for as long as the sun shall rise and the rivers go down to the sea.” They further observed that Alcatraz resembled most Indian Reservations in that it has no fresh running water; inadequate sanitation facilities; high unemployment; and no health care or educational facilities. Furthermore, they wanted the ships that entered the Golden Gate to see Indian land first.

In a separate letter dated December 16, 1969, they invited delegates from every Indian nation to join them. There they wished to establish a Cultural Center, a college, a religious and spiritual center, a museum, a center of ecology, and a training school.

Most of the Native American students who were attending UC Berkeley’s Native American Studies Program were on “The Rock” instead of on-campus attending classes. I had to go out to Alcatraz to meet my student-activists, most of whom eventually returned to school. It was strange to be teaching in Native American Studies and to not have any Native American students.

May 24

Graduated from Oklahoma State University

Graduated from Oklahoma State University, Stillwater with a Master of Arts Degree in English (May 24). I had completed my degree the previous Fall Semester but it was not conferred until the spring commencement, and I was already employed in my first university teaching position.

1972

Accepted tenure track position at the University of Montana

I did not enjoy city living and applied for two positions in Native American Studies at Western Washington University, Bellingham, and the University of Montana, Missoula. I was offered a tenure track position at both and chose the University of Montana.

Appointed Director/Assistant Professor, American Indian Studies, University of Montana

Appointed Director/Assistant Professor, American Indian Studies, University of Montana, Missoula (August). The University eventually changed the name to Native American Studies.

During my first semester of teaching and administrator of American Indian Studies (AIS) at UM, the contingent of the Trail of Broken Treaties, which originated in Seattle came to the University and asked the Kyi Yo Indian Club to assist them with lodging, meals, equipment, and supplies. Next thing I knew, Russell Means invited our Indian students to join the Trail of Broken Treaties and accompany other activists of the American Indian Movement to Washington, D.C.

The Dean of Arts and Sciences, in which AIS was located, agreed to let the fifteen students who wished to join the caravan go, and to also earn fifteen hours of Omnibus credit, provided they did their assigned academic work which consisted of a two-part journal:

- What actually happened, and

- How I felt about it.

He also appointed two other professors to assist me with logistics and evaluation of the journals when they returned.

Transportation was a critical issue and the students raised enough money in several days to purchase three cars. Off they went. The caravans, which had taken different routes simultaneously reached Washington D.C. and when communications with the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) broke down, the activists occupied the BIA building.

This caused me endless concern, but fourteen students and journals eventually returned. On their way back home, the fifteenth student decided to just go home to Wisconsin. We were all so glad to see them return and we had a welcome home feed for them.

We invited John Woodenlegs, Chairman of the Northern Cheyenne Nation to come to deliver a welcome back home speech to the students, and he told them the following:

“Before Custer left the east to take care of the Indian problem out west, the government asked him to return to Washington D.C. and report his findings so they would know how deal with these Indians.” Furthermore, they said “they would do nothing until he came back.”

He added: “We know what happened at the Little Big Horn, and I hope while you were in Washington D.C. you took the time to tell the government that ‘Custer won’t be back. Now they can do something about us Indians!”

We, three professors, decided the students’ journals were so exceptional that we would attempt to have them printed into a book, which we would title Tell Them Custer Won’t be Back based upon Mr. Woodenlegs’ commentary. The Indian Historical Press of San Francisco agreed to publish the book, but when the contract arrived, there were too many liabilities for the students, and we dropped the book idea. The journals are now in the custody of the University of Montana Library.

So much for my first semester at the University of Montana, almost my last, as well. The university had liked the Indian activism I brought to UM.

News Article

1976-1977

Included in Notable Americans of 1976-77

Included in Notable Americans of 1976-77, Raleigh, NC: American Biographical Institute.

1977

Became Interim Director & Lecturer at Harvard University

Took leave from UM to become the Interim Director and Lecturer, American Indian Program, Graduate School of Education, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA (January-June).

July

Promoted to Associate Professor, UM, Missoula

Promoted to Associate Professor, University of Montana, Missoula

1977-1978

Included in “Who’s Who of American Women“

Included in Marquis Who’s Who, Inc., Who’s Who of American Women, Chicago, IL: Marquis, Who’s Who, Inc., 1977-1978.

1978

Included in “The World Who’s Who of American Women in Education“

Included in The World Who’s Who of Women in Education, Cambridge, England, and New York, NY: International Biographical Centre, 1978.

Included in “The World Who’s Who of Women“

Included in The World Who’s Who of Women, Cambridge, England: International Biographical Centre, 1978.

1979

Attended Post-Graduate School at the University of New Mexico, Albuquerque

Granted a three-year leave without pay from the University of Montana, Missoula to attend Post-graduate School at the University of New Mexico, Albuquerque to work toward a doctorate degree (August 1979-June 1982).

Included in the Dictionary of International Biography

Included in the Dictionary of International Biography, Volume XV, Cambridge, England: International Biographical Centre, 1979.

Recipient Danforth Foundation Fellowship

1979-1980 Recipient Danforth Foundation Fellowship, Danforth Foundation, Saint Louis, Missouri. The Fellowship renewed annually in 1980-1981 and in 1981-1982 for study toward a doctorate degree at UNM, Albuquerque.

1980

Alfred Whiteman, Jr. Passed Away

Alfred Whiteman, Jr. passed away at the United States Veterans Hospital, Albuquerque, NM (December 5), after having fought diabetes for many years. The disease eventually resulted in renal failure, necessitating that he go on a dialysis machine, which was installed in our home in Missoula, in our apartment while I was teaching at Harvard, and in our home in Albuquerque. We put him on the dialysis machine at home for five years, but he ultimately died of cardiac arrest.

Death of the men in my family: grandfather, brother, son, and now a husband left sorrow in my heart that time has slightly diminished, but there is an emptiness left by my first friend, baby brother, firstborn, and my beloved husband.

1982

Graduated From The University of New Mexico, Albuquerque

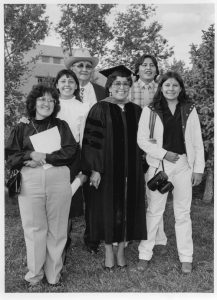

Henrietta Whiteman graduated from the University of New Mexico, Albuquerque with a Doctor of Philosophy Degree in American Studies (May 16).

Title of Doctoral Dissertation: “Cheyenne-Arapaho Education, 1871-1982. It was written under Professor Richard E. Ellis, and later published into a book in 1997.

July

Promoted to Full Professor, UM, Missoula.

Promoted to Full Professor, University of Montana, Missoula.

Named Cheyenne Indian of the Year

Named Cheyenne Indian of the Year, for achievements in education, at the American Indian Exposition, Anadarko, Oklahoma.

1986

Federal Appointment as the Deputy to the Assistant Secretary/Director – Indian Affairs

1986-1987 Granted leave from UM on an Intergovernmental Personnel Assignment (IPA) to assume a federal appointment as the Deputy to the Assistant Secretary/Director – Indian Affairs (Indian Education Programs), Bureau of Indian Affairs, U.S. Department of the Interior, Washington, D.C. I became the highest-ranking woman in Indian Education in the federal government. Testimony at BIA Education Budget Hearings on The Hill was intimidating.

One of the most memorable events of my year in Washington, D.C. as the Director of Office of Indian Education Programs was the trip my Anadarko Area Office Line Officer, Dr. Carolyn Elgin and I made to the Sac & Fox community located in Nacimiento, Mexico. At their request, the parents and tribal leaders were concerned about having to withdraw their children from school while they followed the fruit harvest in the United States. They wanted to keep the family intact. They were interested in the possibility of having the BIA-OIEP purchase and equip a large bus as a travelling school. I liked the idea, especially about keeping the family together but the BIA was not receptive to this idea. Ultimately the children’s education suffered and their families were separated as parent(s) followed the seasonal harvest.

September 1

Attended The First Feast Held In Honor Of Oakerhater At The Washington National Cathedral

My aunt June Wolftongue and I attended the first feast held in honor of Oakerhater at the Washington National Cathedral in Washington, D.C. on September 1, 1986. The Episcopal Church had designated him as a Saint in 1985, making him the first Native American and Oklahoman to become a Saint in the Episcopal Church. On that feast day, my aunt and I carried the Christian elements for communion to the altar, and afterward joined other family members and the Oklahoma delegation for the service, parts of which were spoken in the Cheyenne language by Chief Lawrence Hart, an ordained minister.

Oakerhater is an anglicized version of the Cheyenne word hoxéhetan, which means a man who sun dances, which he translated as “Making Medicine.” He was the middle child of three brothers and his younger one was Wolf Tongue. My mother Lenora Wolftongue was Oakerhater’s great-niece or granddaughter in the Cheyenne way, making me his great-great niece or great-granddaughter according to the Cheyenne kinship system.

Unfortunately, as a young man, he was one of eighteen innocent men forced to join the other warriors, who had been identified to become prisoners of war. Thirty-three Cheyenne and two Arapaho were shackled and chained into wagons that went south to Fort Sill to join some Caddo, Comanche, and Kiowa militants, which resulted in a total of seventy-two prisoners of war. In 1875 they were sent into a three-year exile to Fort Marion, an abandoned Spanish fortress in St. Augustine, Florida.

Their jailor was Richard Henry Pratt, who later established the Carlisle Indian Industrial School in Pennsylvania.

When the POWs were released three years later, most returned home to Indian Territory but Oakerhater went north to New York where he studied theology (Scripture), current events, and agriculture. His sponsors were Senator George H. Pendleton and his wife, the former Alice Key, who was the daughter of Francis Scott Key. He was later baptized, confirmed, and ordained an Episcopal deacon in 1881. By that time, he had taken the name David Pendleton Oakerhater, which came from the Bible, his sponsors, and his Cheyenne heritage.

Nine of the Cheyenne and Arapaho prisoners were sent to Hampton Institute, which had been established by Samuel C. Armstrong as an industrial training school for freed Black slaves. Armstrong contended in an 1880 Report of the Commissioner that although the manual-labor education system was expensive, it was cheaper than extermination.

Now a deacon, Pratt requested Oakerhater to recruit American Indian students in Indian Territory for his Carlisle School. Oakerhater eventually returned home to Indian Territory, and in 1889 began his ministerial work at Whirlwind Mission near Fay, Oklahoma from which he retired in 1918. He lived for a short time in Clinton, Oklahoma, and eventually moved to Watonga, Oklahoma where he died in 1931.

David Pendleton Oakerhater was a Cheyenne warrior, Bow String Society member, prisoner of war, artist, ordained deacon, preacher, Cheyenne chief, a medicine person true to his name “Making Medicine,” and eventually an Anglican Saint.

1987

Chose To Resign My Position As Deputy To The Assistant Secretary/Director Of OIEP

After one year of working with the BIA in Washington, D.C., I chose to resign my position as Deputy to the Assistant Secretary/Director of OIEP because of my political and philosophical differences with the administration. I was a Democrat in a Republican administration.

The Assistant Secretary, consequently modified my IPA and I returned to Missoula, MT to work in the field on the OIEP Alcohol & Substance [Abuse] Initiative. I was Field-Based for six months from January-July 1987.

Returned To Position As Director/Professor, Native American Studies

Returned to position as Director/Professor, Native American Studies, University of Montana, Missoula, MT (August).

1990

June-December

Internal Sabbatical, UM, Missoula

Internal Sabbatical, University of Montana, Missoula

1991

March 21

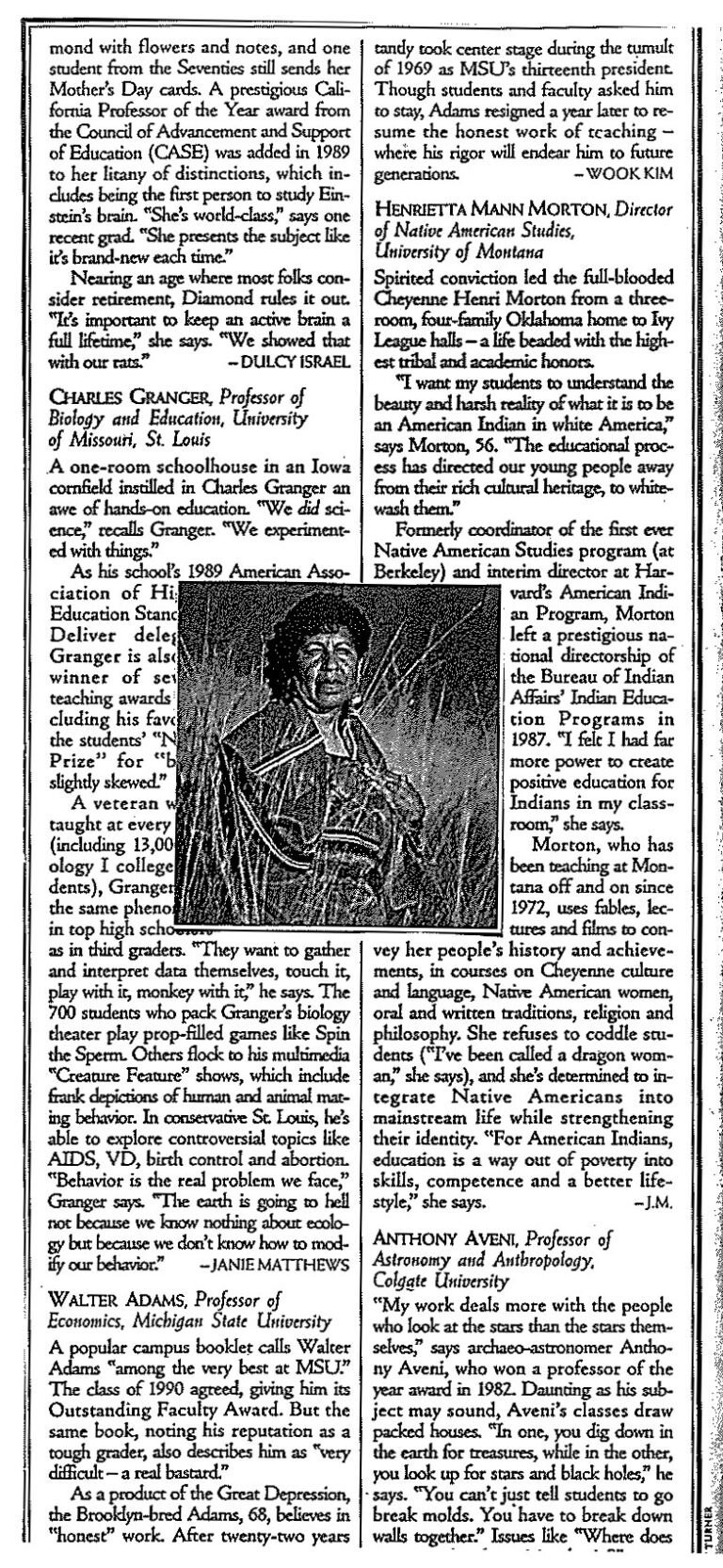

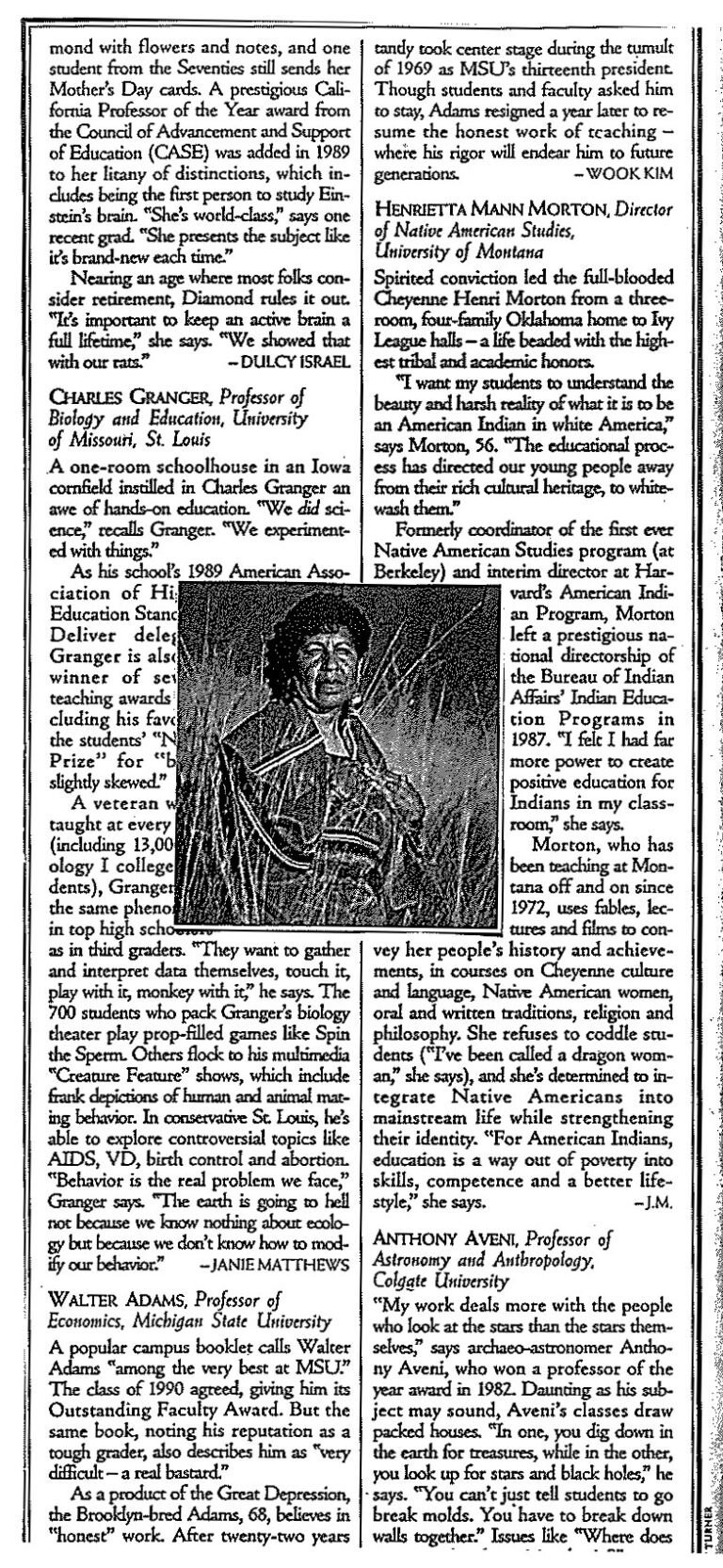

Named To The Honor Roll Of Top Professors Nationwide, Rolling Stone Magazine

Named to the Honor Roll of [Ten] Top Professors Nationwide, Rolling Stone Magazine, Special College Issue, March 21, 1991.

When the news was made public, one of my colleagues from across campus wrote me a short note stating: “For holdover hippies like us from the ’70s, inclusion in Rolling Stone, is our equivalent to a Nobel Laureate.”

May 8

Eugene M. Kayden Award

Eugene M. Kayden Award (Best Manuscript in the Humanities), University Press of Colorado, Dissertation, Cheyenne-Arapaho Education: 1871-1982, Boulder, CO: University Press of Colorado, Boulder, May 8, 1991.

National Coordinator, American Indian Religious Freedom Coalition and Director AIRFA Project

1991-1992 National Coordinator, American Indian Religious Freedom Coalition and Director AIRFA Project, Washington, D.C. Office, Association on American Indian Affairs, NY, NY. I was based in the Washington D.C. office of the Native American Rights Fund (NARF).

It was the goal of the Coalition to get four legislative amendments to the American Indian Religious Freedom Act (AIRFA) of 1978, which had been passed by the U.S. Congress as a joint resolution. It was my responsibility to build the support for Congressional passage (a monumental task). The proposed amendments were:

- Protection of Indian sacred sites,

- Protection of traditional use of peyote by Indians,

- Protection of religious rights of Indian prisoners to the same extent as prisoners of other religious faiths, and

- Protection of religious use of eagles and other animals and plants.

AIRFA came about as a result of religious rights violations of American Indians. In reality, it is nothing more than a weak attempt, described as a “toothless tiger,” to extend First Amendment protection to indigenous people. Proposed amendments were eventually introduced in the Senate as the Native American Free Exercise of Religion Act of 1993 but were never enacted.

Some Cherokees attempted to stop the Tennessee Valley Authority from completing the construction of the Tellico Dam. The dam would flood their birthplace as a people, Chota their historic capital, burial places, and places where they gathered their sacred medicines. This group filed a lawsuit Sequoyah v. Tennessee Valley Authority, and sought relief under AIRFA, but lost. This case became the first Indian sacred site case lost after the passage of AIRFA.

This case was followed by the devastating 1988 Supreme Court ruling in the case of Lyng v. Northwest Indian Cemetery Protective Association. The Yurok, Karok, and Tolowa Indians of Northern California attempted to stop the U.S. Forest Service from the construction of a six-mile paved road between Gasquet and Orleans (GO Road) in the Chimney Rock area of the Six Rivers National Forest, where the three Northern California nations hold their renewal ceremonies.

Christopher Peters, Yurok spokesperson concludes: “This precedent-setting case established that Native Americans do not have First Amendment protection under the United States Constitution. . . . Lyng [Secretary of the Interior, Richard E. Lyng] deems that the total destruction of three Native American religions . . . is not a violation of the First Amendment Free Exercise Clause.”

Two years later in 1990, the Supreme Court handed down another equally devastating decision in the Employment Division, Department of Human Resources of Oregon v. Smith

et al, which involved the Native American Church and its traditional use of peyote. The Supreme Court ruled in favor of the State of Oregon and did not apply the “compelling state interest” test applicable to free-exercise cases.

So again, the First Amendment did not protect a Native American religious practice with a lengthy history on this land because of its sacramental use of Peyote. The Supreme Court directed all concerned, including mainstream churches, to go to Congress for a religious remedy.

Mainstream churches pursued their own legislative remedy, which ultimately resulted in the passage of The Religious Freedom Restoration Act of 1993, Public Law 103-141, which restored religious freedom to all Americans. It, however, did not go far enough in protecting the unique, unwritten, and often misunderstood needs of American Indians in the free exercise of their religious practices.

Reuben Snake, respected Winnebago Road Man, his attorney James Botsford, the AIRFA Coalition, along with some church groups went back to work. Their efforts ultimately resulted in Congress passing Public Law 103-344, the American Indian Religious Freedom Act Amendments of 1994, which related to the “Traditional Indian Religious Use of the Peyote Sacrament.”

With this legislation, one of the four sets of legislative amendments became law. It must also be recognized that AIRFA did result in the enactment of the 1990 Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA), which addresses the return of human skeletal remains and sacred objects to their cultural homelands.

1992

International Women’s Day

International Women’s Day

- Workshop presenter, “The Native American Woman,” and Panelist/Speaker, General Assembly, Phoenix, AZ, March 8, 1992.

- “Dr. Henrietta Mann: Native American Recognizes Cultural Diversity,” Featured in Today’s ARIZONA WOMAN: Success Magazine, March 1992.

Speaker, First Greifswald Conference

Speaker, First Greifswald Conference on “Peoples in Contact, Remembering the Past – Sharing the Future,” Institute for English and American Studies of the Ernst-Moritz-Arndt University, Greifswald, Germany, June 19, 1992.

Presenter, “Environmental and Spirituality” Workshop

Presenter, “Environmental and Spirituality” Workshop, Environmental Grantmakers Association, 1992 Fall Retreat, Orcas Island, San Juan Archipelago, October 3, 1992.

1993

Included in “Native American Women, A Biographical Dictionary“

Included in Bataille, Gretchen M., Native American Women, A Biographical Dictionary. New York: Garland Publishing, 1993.

Panelist On “Minority Religious Practices: Where Does the State Draw the Line?”

Henrietta Mann was a panelist on “Minority Religious Practices: Where Does the State Draw the Line?” (March 17) at the conference titled Religious Liberty in America: Crossroads or Crisis? It was held at The Freedom Forum World Center, Arlington, VA, sponsored by The Freedom Forum First Amendment Center at Vanderbilt University.

Speaker, “The West”

Speaker, “The West,” the Sixth Annual A Giving of Thanks to the First Peoples “With One Heart,” Fund of the Four Directions Thanksgiving Project and the Cathedral of St. John the Divine, New York, NY, November 20, 1993.

Visiting Professor, Natural And Social Sciences; Interim Dean of Instruction, Haskell Indian Nations University

1993-1995 Intergovernmental Personnel Assignment (IPA) Visiting Professor, Natural and Social Sciences (Indian Studies); and Interim Dean of Instruction, Haskell Indian Nations University (HINU), Lawrence, KS

HINU has some wetlands on the southern boundary of the campus, which some HINU faculty (including me) and students sought to protect from development. Further, a sacred earthwork in the shape of a medicine wheel is situated near the wetlands. The State of Kansas proposed construction of a thoroughfare around the city of Lawrence, which would cut right through the wetlands and desecrate this sacred site. The struggle to “Save the Wetlands” lasted many years, but I understand this road has been built, once again resulting in religious infringement and violation of another Indian sacred site.

1994

Panelist, “American Indian Women,” Festival on The American West

Panelist, “American Indian Women,” Festival on The American West coordinated in the U.S. by the American Indian College Fund for Palazzo delle Esposizioni, Rome, Italy, January 12-18, 1994.

2000

Visiting Elder, Native American Environmental Awareness Summer Youth Practicum

Visiting Elder (Instructor/Speaker), 2000 Native American Environmental Awareness Summer Youth Practicum, Native American Fish & Wildlife Society, Mt. Evans Outdoor Education Laboratory, Evergreen, CO, July 28, 2000.

Accepted The Position Of Katz Endowed Chair Of Native American Studies, Montana State University, Bozeman

After advancing through the academic ranks to full Professor at the University of Montana, Missoula left a tenure track position to accept the position of Katz Endowed Chair of Native American Studies in the Center for Native American (CNAS) College of Letters and Science at Montana State University (MSU)-Bozeman. Became the first occupant of the Katz Endowed Chair in NAS.

2001

February 8

Closing Address, State of the Tribal Nations Address, Joint Session, 57th Legislature, Montana

Closing Address, State of the Tribal Nations Address to the Bicentennial Legislative Assembly, Joint Session, 57th Legislature, State of Montana, House Chambers, State Capitol, Helena, MT, February 8, 2001.

February 8

Governor’s Humanities Award

Governor’s Humanities Award given by Judy Martz, first female Governor of the State of Montana in association with the Montana Committee or the Humanities, Capitol Rotunda, Helena, MT, February 8, 2001.

April 20

Keynote Speaker “This Is Sacred Land: Native Spiritual Practices and the Sacred Mother Earth”

Keynote Speaker, “This Is Sacred Land: Native Spiritual Practices and the Sacred Mother Earth,” Opening Plenary Session THE SACRED EARTH CONFERENCE: Building Alliances to Protect Sacred Lands, Seventh Generation Fund, Seattle, WA, April 20, 2001. (Following this, I became a member of their Board of Directors)

October 10

Benediction, Presidential Inaugural Convocation of Geoffrey Gamble

Benediction, Presidential Inaugural Convocation of Geoffrey Gamble, 11th President of Montana State University, Bozeman, October 10, 2001

November 13

Offered Prayer at Ground Zero, New York, NY

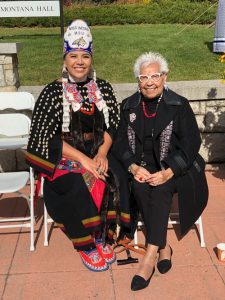

Offered Prayer at Ground Zero (World Trade Center), New York, NY, assisted by Montoya Whiteman, arranged by film actor Richard Masur with the American Red Cross, Brooklyn, NY (November 13). Afterward, Richard gave me his hard hat which I had to wear during the ceremony we held at the edge of the pit under the big red crane. I was told that the crane stopped for the entire time we were offering prayers.

Personal Feelings: At the suggestion of Gail Small, Program Director SAL

I was scheduled to be in New York City for an event of the American Indian College Fund and mentioned this to my friend Richard Masur, whom I had met when I was doing sacred sites work with the American Indian Religious Freedom Coalition. The AIRFA Coalition had an event at the University of Arizona, Tucson, specifically to discuss maintaining the sanctity of Mount Graham. The San Carlos Apache call it “Big Seated Mountain,” which is the home of their Spirit Crown Dancers and is the gateway for their prayers. Nonetheless, the Mount Graham International Observatory was being built.

After 9/11, Richard had been working with the firemen and others excavating the pit at the bottom of what had been the World Trade Center. He was bothered by the fact that every denomination in the country had been there to pray, except for this land’s first peoples. He arranged for us to pray at Ground Zero. Accompanied by a Chaplain and Public Information Officer, we all climbed on a UTV, Recreational Off-highway vehicle. Richard drove, I was the passenger, and the three others climbed onto the rear bed, some feet dangling off the back. We wore hard hats, but the five of us did not wear gas masks (respirators).

I will never forget my first sight of the wreckage and the smoldering pit. Someone rushed up and told us that we had come at the right time as they had just found another body! I thought “there is so much to pray for.” Attempting to control my emotions I thought “so this is how a war-torn place looks.” Even most of the buildings still standing on the periphery were blackened by fire and showed structural damage.

I thought of the number of lives lost there. I could not begin to fathom the horror of their last minutes, the grieving families left behind, the rescue workers who dug through the rubbish in search of people, and the heroes who died there—those that lived. My heart all but broke, as I witnessed the aftermath of cruelty that defies description by those who blatantly committed this heartless act. I silently asked myself “Why? Why?”

We had specifically asked that the Mohawks, some of whom had helped build the Twin Towers, to join us in the ceremony. As it usually is, they were doing the most dangerous work. They sent two representatives, a man, and a woman to join us in ceremony. And so we burned cedar and offered prayers to Ma’heo’o and to the sacred beings who sit at the four directions of the world, as well as up and below. I also sang my prayer song. We are taught that tears are the highest form of prayer, and that day mine was the highest of prayer but offered in a most humble, pitiful way. That day I learned what death is and the true meaning of inhumanity.

The ceremony concluded, we climbed back on the UTV and returned to the outside faucets located alongside the building where the rescue workers slept. We washed our shoes and hands. I looked back toward the big red crane working directly over the pit at Ground Zero. Then I turned to walk away with my daughter and friend. We walked in silence, absorbed with our many thoughts and a new experience. I understood what my father, a World War II veteran, meant when he said “war is terrible.”

Richard took us to eat at a small Mexican restaurant, saying “this is the nearest to a native meal I can offer you.” We ate in silence. I left a part of myself in that hallowed ground, and can never forget the experience of having seen the aftermath of what war looks like and having glimpsed into the cruel depths of murder committed by those dedicated to their own beliefs and actions.

I can only hope this has made me more compassionate, loving, and kind. I also relish peace, honor life, and see with the eyes of my heart. I also understand my name variously translated as “Prayer Cloth Woman,” “The Woman Who Comes to Offer Prayer,” or “Prayer Woman.”

November 12-14

Washita Symposium: Past, Present and Future

Washita Symposium: Past, Present and Future, Proceedings of Symposium, November 12-14, 1998, United States Department of the Interior, NATIONAL PARK SERVICE, Washita Battlefield National Historic Site, Cheyenne, Oklahoma, December 2001.

Honorary Advisory Council

2001-2006 Honorary Advisory Council of 100 Scholars, Leaders and Chiefs-Traditionalists, American Indian Graduate Center, Albuquerque, NM.

2002

Guest Writer, “Reflections of a Cheyenne Woman: Ground Zero“

Guest Writer, “Reflections of a Cheyenne Woman: Ground Zero,” NARF Legal Review, Native American Rights Fund, Vol. 27, No. 2, Summer/Fall 2002.

Elder in Residence and Member of Governing Council, National Institute for Native Leadership in Higher Education

Elder in Residence and Member of Governing Council, National Institute for Native Leadership in Higher Education (NINLHE), Summer Institute, Santa Ana Pueblo, NM, August 2-6, 2002.

Panelist, “Preserving Indian Cultural Integrity”

Panelist, “Article I, Section 1(2), Preserving Indian Cultural Integrity,” 30th Anniversary Celebration of the Montana Constitution, House Chambers, Montana State Capitol, Helena, June 22, 2002.

2003

Professor Emerita, Native American Studies

Professor Emerita, Native American Studies, Montana State University, Bozeman.

Special Assistant to the President, MSU

2003-2016 Special Assistant to the President, Office of the President, Montana State University, Bozeman.

Visiting Elder and Speaker, Harvard University Native American Program

Visiting Elder and Speaker, “Native American Spirituality and Education,” Harvard University Native American Program (HUNAP), Graduate School of Education, Cambridge, MA, February 10-11, 2003.

Delivered the Commencement Charge to the graduates of MSU

Delivered the Commencement Charge (address) to the graduates of the Hundred and Seventh Annual Commencement of Montana State University, Bozeman, May 2003.

May 22

Speaker, St. Labre Catholic Indian School

Speaker, St. Labre Catholic Indian School, 2003 Commencement, Ashland, MT, May 22, 2003.

Earth Mother and Prayerful Children: Sacred Sites and Religious Freedom

“Earth Mother and Prayerful Children: Sacred Sites and Religious Freedom,” in Richard A. Grounds, George E. Tinker and David E. Wilkins, eds. Native Voices: American Indian Identity & Resistance. Book dedicated to Vine Deloria, Jr. Lawrence: University of Kansas Press, 2003.

Co-author, “Culture and Language Matters: Defining, Implementing and Evaluating“

Prologue “Elder Reflections” and Co-author with Maenette K.P. Ahnee-Benham, Chapter 9, “Culture and Language Matters: Defining, Implementing and Evaluating,” in Maenette K.P. Ahnee-Benham and Wayne J. Stein, eds. The Renaissance of American Indian Higher Education: Capturing the Dream. Mahwah, New Jersey, Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Publishers, 2003.

Guest Editorial, Winds of Change, American Indian Education & Opportunity

“Education as Protection,” Guest Editorial, Winds of Change, American Indian Education & Opportunity, Boulder: CO: AISES Publishing, Inc., Winter 2003.

Opening Keynote Speaker, National Conference on Race & Ethnicity in American Higher Education

Opening Keynote Speaker, 16th Annual National Conference on Race & Ethnicity in American Higher Education (NCORE), convened by the University of Oklahoma (Norman), Southwest Center for Human Relations Studies, San Francisco, CA (May 27-31, 2003.

Speaker, Oxted and vicinity of London, England

Speaker, Oxted and vicinity of London, England. I was, also one of two American Indian ceremonial people, who led the group “Peace through Education,” in a sunrise ceremony at Stonehenge, Wiltshire, English, Salisbury Plain, which is a designated English Heritage Site. We were granted permission to enter inside the circular stone structure and offer a pipe in prayer. November 15, 2003.

2004

National Museum of the American Indian transferred the human remains in its collections

(Year is an estimate only) The National Museum of the American Indian (NMAI) transferred the human remains in its collections from the Bronx, NY to the Smithsonian’s Support Center in Suitland, MD.

Jim Pepper Henry and Terry Snoball of the NMAI were in charge of the transfer, who brought in four spiritual knowledge keepers from Indian Country to assist in the transfer. They were:

Jerry Flute and Joe Williams, Sisseton-Wahpeton Dakota;

Montoya Whiteman and Henrietta Mann, Cheyenne and Arapaho Tribes;

A Will to Survive: Indigenous Essays on the Politics of Culture, Language, and Identity

Mann, Henrietta. “Of This Red Earth,” in Stephen Greymorning, ed. A Will to Survive: Indigenous Essays on the Politics of Culture, Language, and Identity. New York: McGraw-Hill, 2004.

Invocation Commencement, MSU

Invocation, Hundred and Eighth Annual Commencement, Montana State University, Bozeman, May 8, 2004.

2006

Speaker, Leiden University, Leiden, Kingdom of the Netherlands

Speaker, Leiden University, Leiden, Kingdom of the Netherlands, North Holland, September 25-October 5, 2006,

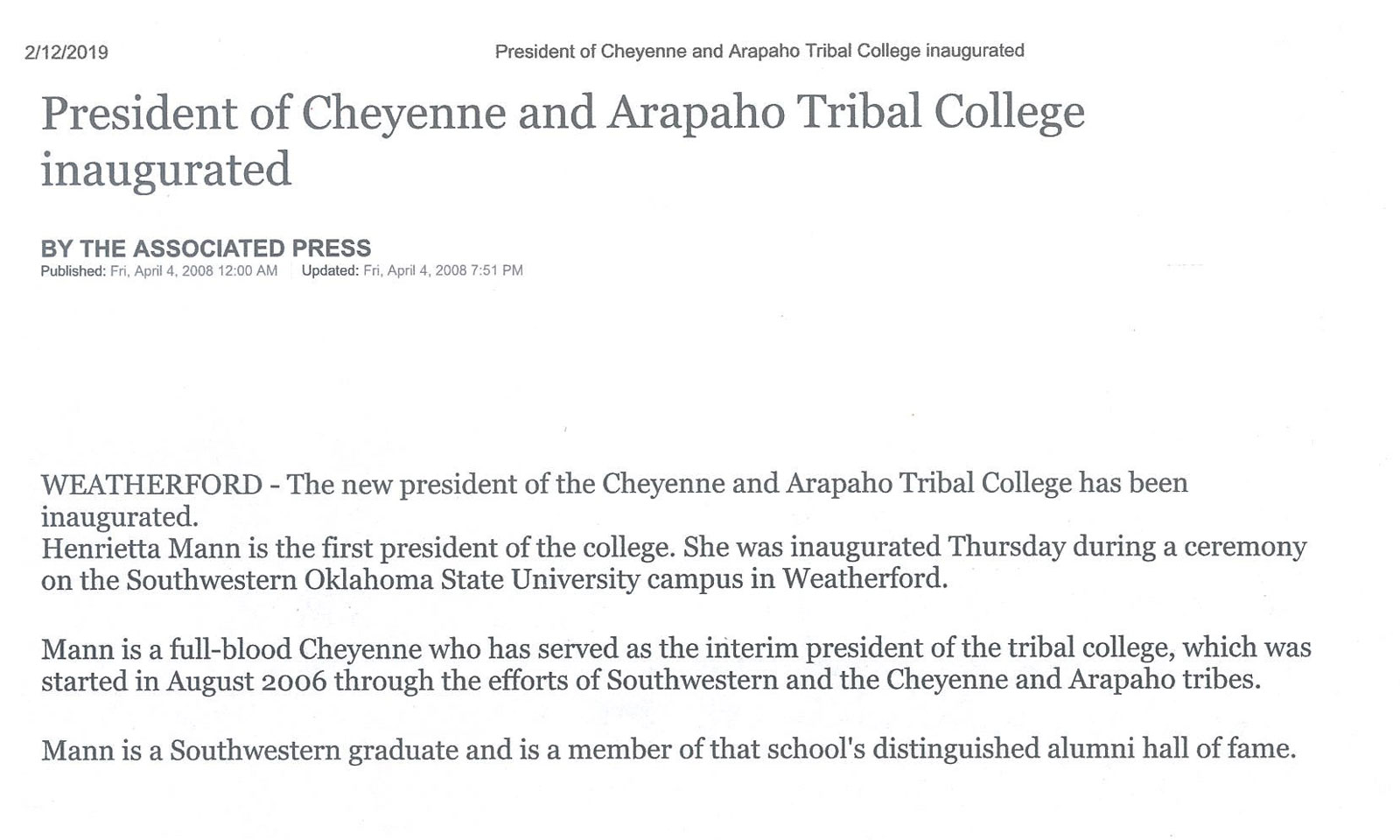

Interim President, Cheyenne and Arapaho Tribal College

2006-2007 Interim President, Cheyenne and Arapaho Tribal College (June 2006-December 2007)

2007

Introduced Al Gore at the Opening Ceremony, MOTHER EARTH: A Special INDIAN SUMMER SHOWCASE

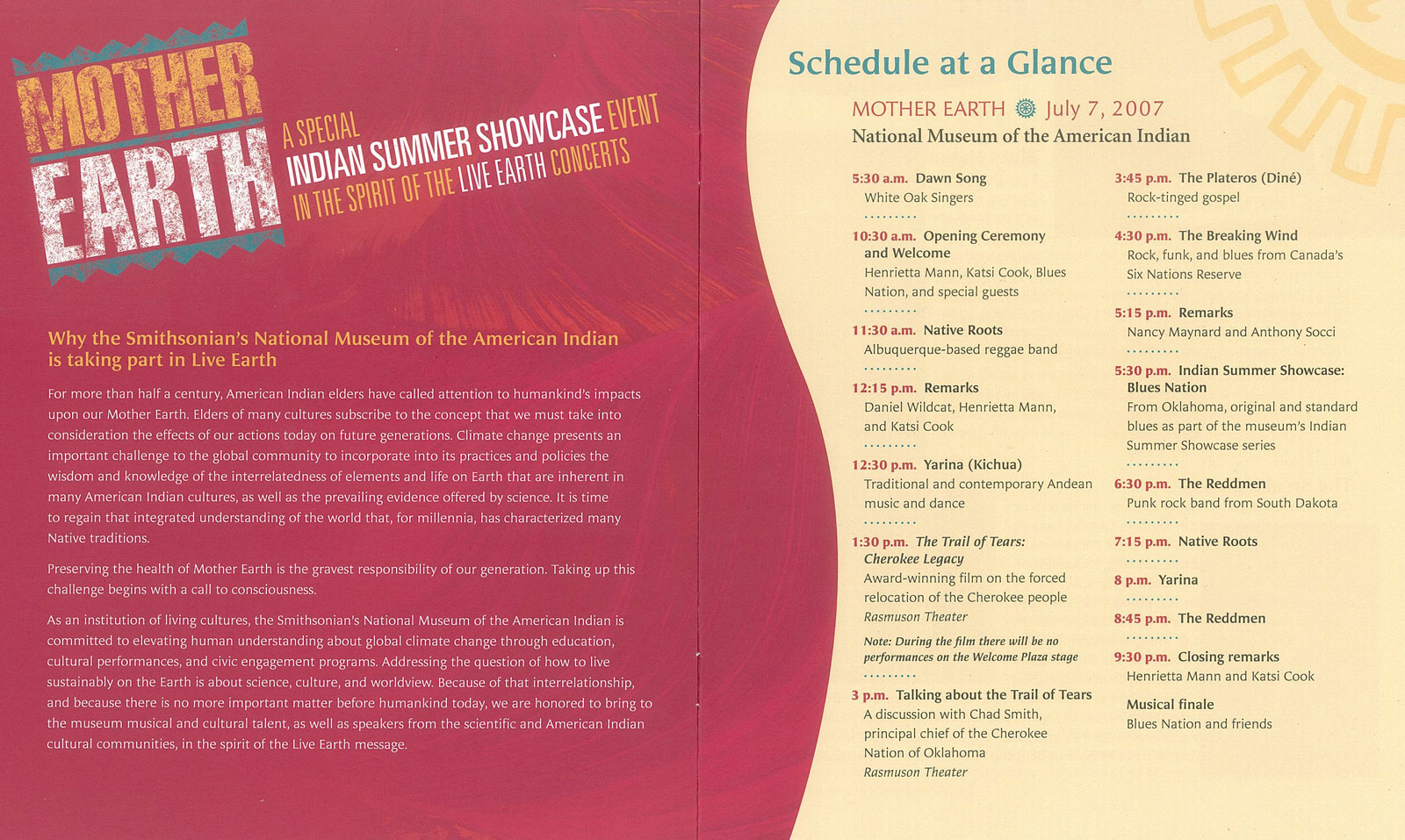

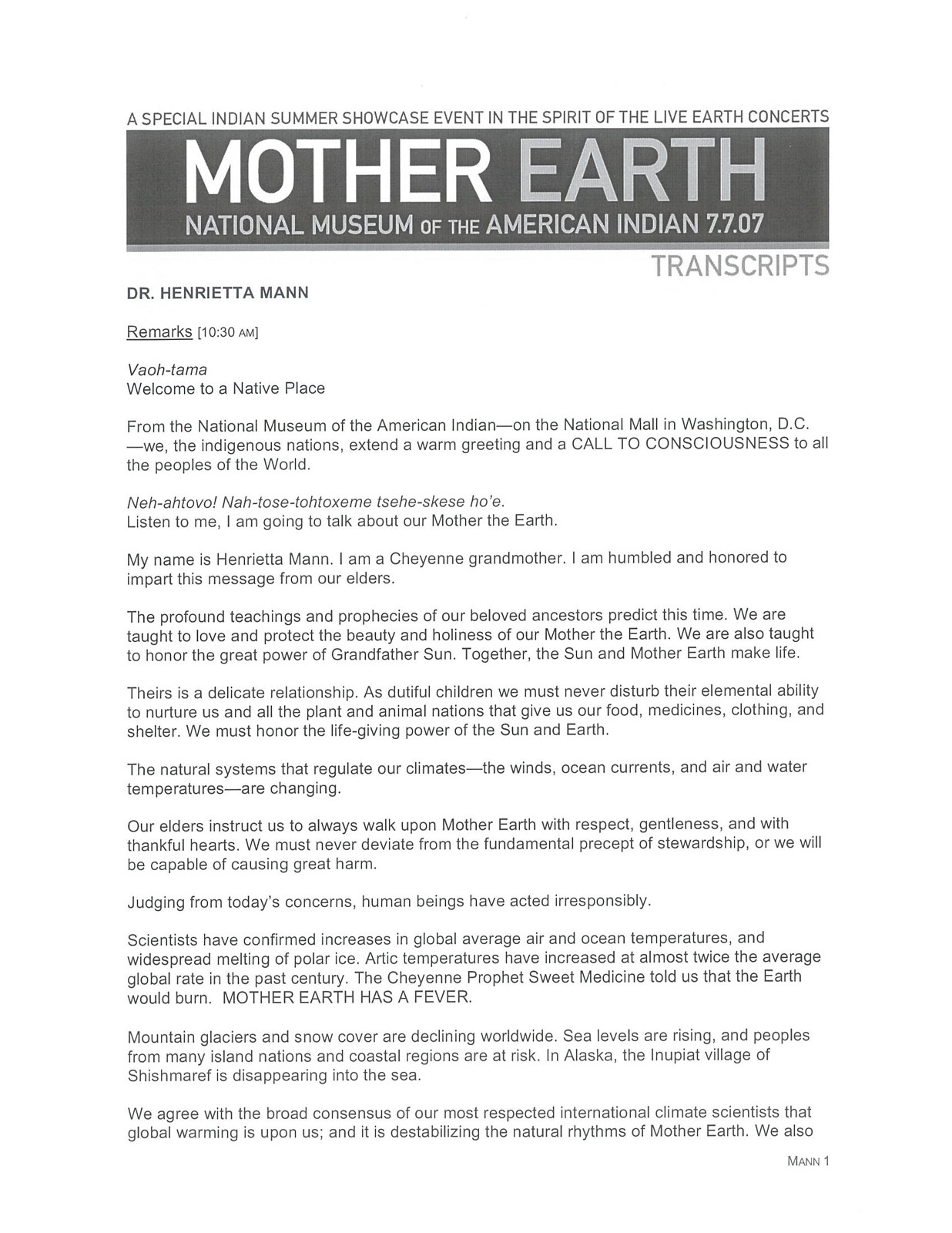

Katsi Cook and I, Guest Speakers, introduced Al Gore at the Opening Ceremony, MOTHER EARTH: A Special INDIAN SUMMER SHOWCASE Event in the Spirit of the LIVE EARTH Concerts, Washington, D.C. Mall: Smithsonian Institution, National Museum of the American Indian, Tim Johnson, Director, Saturday, July 7, 2007.

2008

Bernard S. Rodey Award

Bernard S. Rodey Award for leadership, vision, and inspirational guidance in Native American education, University of New Mexico Alumni Association, Albuquerque, NM.

Lifetime Achievement Award

National Indian Education Association Lifetime Achievement Award for achievement and service to Native education, 39th Annual NIEA Convention, Seattle, WA.

Selected to sit on the dais with the Dalai Lama

Invited by the Lummi Nation of the State of Washington to be a part of the Native American delegation that was to attend the Dalai Lama’s public speaking events in different places in Seattle where he was to be honored and to meet privately with him at his request. I was among the few selected to sit on the dais with the Dalai Lama as he spoke on COMPASSION to the audience assembled at Seattle’s Quest Field.

The city is named for Chief Seattle, the great Suquamish and Duwamish leader from that place, who is credited with saying: “We do not inherit the earth from our ancestors; we borrow it from our children.”

We were informed in our briefing session not to touch the Dalai Lama, but as we walked up the steps to join him on the dais, he rose from his special chair, which is transported to all his speaking engagements. As the Native American delegation came onto the platform, the Dalai Lama rose and shook hands with all of us Native American delegates, who sat on the platform with him.

2009

Legacy Award Winner

Legacy Award Winner for the education of Native American women and men, Working Mother Media, A Division of Bonnier Corporation, 7th Annual Best Companies for Multicultural Women National Conference, New York, NY.

Narrative writer for We Waited for You: A Welcome Baby Book

Mann, Dr. Henrietta. Narrative writer for We Waited for You: A Welcome Baby Book. Photographs: Cheyenne and Arapaho Children. eds. Sharon Connor and GordonYellowman. Concho, OK: Cheyenne and Arapaho Publishing, 2009.

2011

“Sand Creek Massacre,” in Encyclopedia of the GREAT PLAINS

Mann, Henrietta. “Sand Creek Massacre,” in Encyclopedia of the GREAT PLAINS, Lincoln: University of Nebraska, Center for Great Plains Studies, 2011.

2012

On This Spirit Walk: The Voices of Native American and Indigenous Peoples

Mann, Henrietta and Anita Phillips. On This Spirit Walk: The Voices of Native American and Indigenous Peoples. A Small Group Curriculum Resource. Muskogee, OK: Native American Comprehensive Plan, the United Methodist Church, 2012.

Ely S. Parker Award

Ely S. Parker Award, American Indian Science and Engineering Society (AISES), 2012 National Conference, Anchorage, AK, November 1-3, 2012.

2013

Lifetime Award Winner

Lifetime Award Winner (First), College Board, Native American Student Advocacy Institute (NASAI), The University of Montana and Salish Kootenai College, Montana, May 30-31, 2013. NASAI subsequently created the Dr. Henrietta Mann Leadership Award to acknowledge and thank leaders for their advocacy in improving lives within native communities.

2013

Opening Keynote Speaker, University of Leiden

Opening Keynote Speaker, University of Leiden, 35th American Indian Workshop, “Tribal Colleges and Universities: Voices for Tomorrow, Leiden, The Netherlands,

May 21, 2014. The organizers of the event and invited guests celebrated my birthday with me, with song, cake, ice cream and gifts, which was a pleasant surprise as I was so far from my family and home on Turtle Island.

2015

President Emerita, Cheyenne and Arapaho Tribal College

President Emerita, Cheyenne and Arapaho Tribal College at Southwestern Oklahoma State University, Weatherford, OK. The Cheyenne and Arapaho Tribes defunded the tribal college, necessitating its closure in June 2015.

Honorary Professor Emeritus, Southwestern Oklahoma State University, Weatherford.

2016

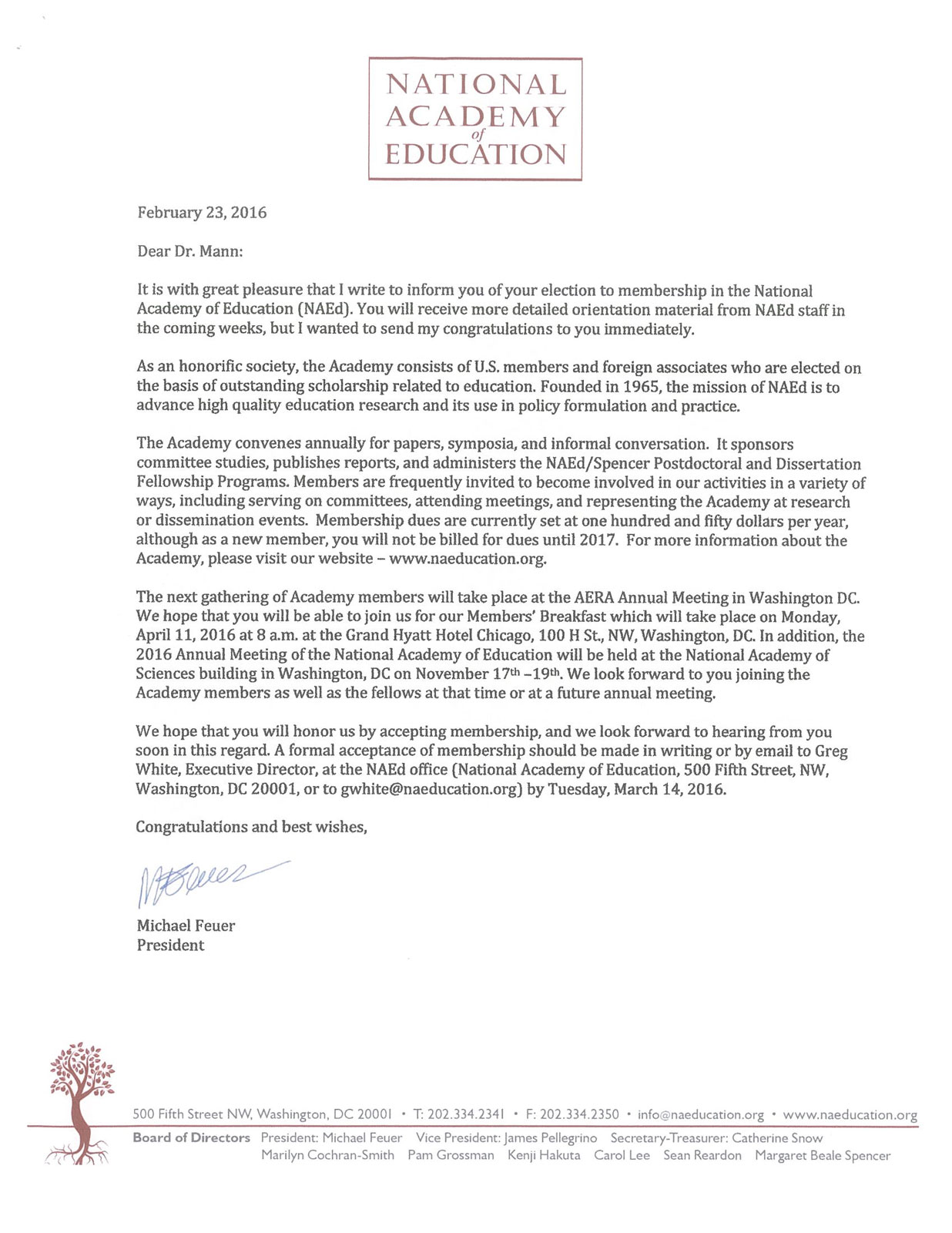

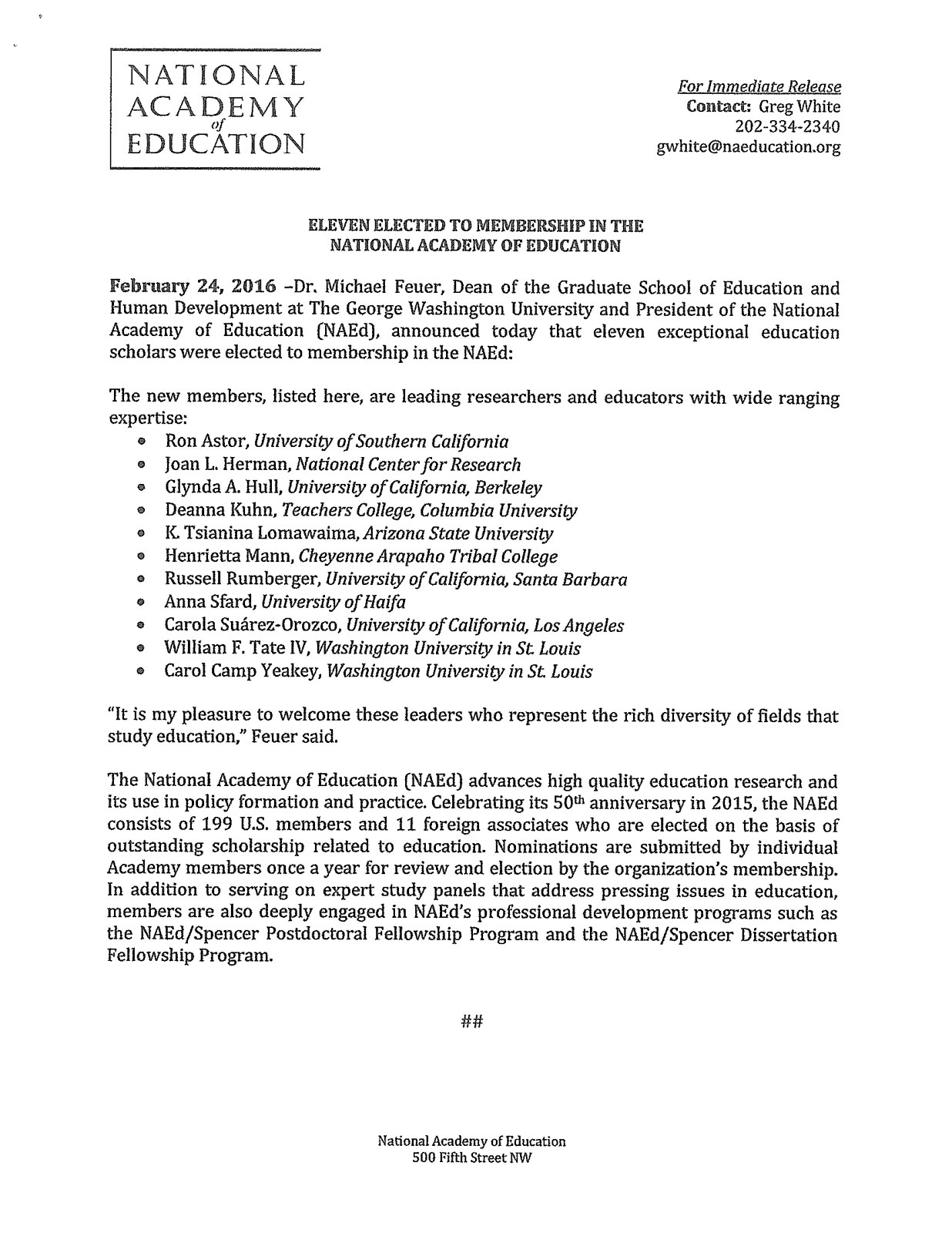

Elected to membership in the National Academy of Education

Became one of two Native American educational scholars ever to be elected to membership in the National Academy of Education.

Listed as one of The 2016 50 FACES OF INDIAN COUNTRY

Listed as one of The 2016 50 FACES OF INDIAN COUNTRY, Indian Country Today, September/October 2016.

2017

Featured in “Our Native Traditions“

Featured in the Spring 2017 edition of Our Native Traditions published by The Shawnee News-Star, Shawnee, OK. Title of the article is “CHEYENNE & ARAPAHO, Dr. Henrietta Mann, a living legend among the Cheyenne and Arapaho Tribes,” written by Rosemary Stephens.

An excerpt from one of the two MSU Presidents for whom I served as Special Assistant for twelve years was quoted in the article:

“Montana State University President Waded Cruzado said that Mann’s ability to stand easily in both the Native and the academic worlds have allowed her an unprecedented impact in promoting respect and understanding across the wold [sic] of Native American culture, history and spirituality.

I once heard her called the “Native Maya Angelou,’ and for good reason, Cruzado said: ‘to hear Dr. Mann speak is to never forget her grace and power.”

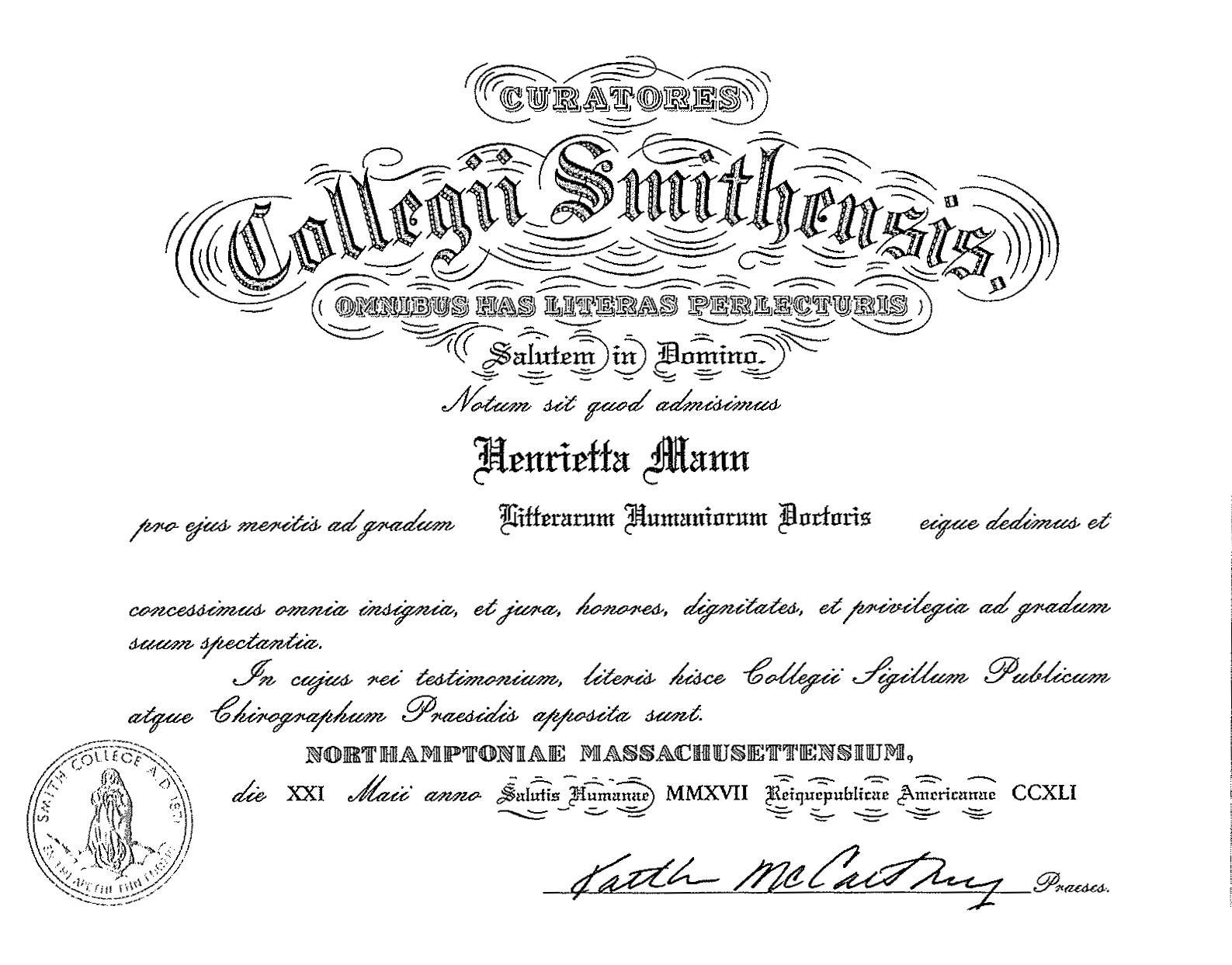

Honorary Doctor of Humane Letters

Smith College, Northampton, MA conferred Honorary Doctor of Humane Letters, their citation reading in part:

“You have said that your life has been ‘lived in the trenches of education with the goal of helping to create a just world in which indigenous cultures thrive and our youth learn what it is to be human.’”

Selected as one of the inaugural circle of eight SPIRIT ALIGNED Legacy Leaders

Selected as one of the inaugural circle of eight SPIRIT ALIGNED Legacy Leaders of Elder women supported by the Spirit Aligned Leadership Program and NoVo Foundation, which includes fiscal sponsorship of Rockefeller Philanthropy Advisors.

2018

January 8-14

Elder and Northern Cheyenne History Presenter

Yellow Bird 400-Mile Spiritual Run, Fort Robinson NE to Montana, Elder and Northern Cheyenne History Presenter, January 8-14, 2018.

February 5

Signed “Contributor Agreement” for article “Of This Red Earth“

Signed “Contributor Agreement” on February 5, 2018 with Routledge: London and New York for the inclusion of my article “Of This Red Earth,” in the book edited by Neyooxet Greymorning.

The book was published: Neyooxet Greymorning, ed. Being Indigenous: Perspectives on Activism, Culture, Language and Identity. London: Routledge, 2019.

Circle of Honor Award/Inductee

Circle of Honor Award/Inductee, American Indian FESTIVAL OF WORDS, American Indian Resource Center-Tulsa-City-County Library-Tulsa Library Trust, Zarrow Regional Library, Tulsa, OK, March 3, 2018.

March 25

Speaker, Women’s History Month

Speaker, “White Buffalo Woman: A Granddaughter’s Perspective,” Women’s History Month, Washita Battlefield National Historic Site, Cheyenne, OK, March 25, 2018.

March 27

Inducted into Oklahoma Historians Hall of Fame

Inducted into Oklahoma Historians Hall of Fame, Oklahoma Historical Society, Annual Awards 2017, Oklahoma City, OK, April 27, 2018.

April 30-May 1

One of the featured panelists, Cultural Foundations of Indigenous Self-Determination

One of the featured panelists, Cultural Foundations of Indigenous Self-Determination, The Next Horizon: A Symposium on the Future of Indigenous Nation Building, John F Kennedy School of Government, Harvard University, Cambridge, Massachusetts, April 30-May 1, 2018.

October 6-7

Induction into the American Academy of Arts & Sciences

Induction into the American Academy of Arts & Sciences, Class III: Social Sciences, 2018 Induction Programs, Sanders Theatre, Harvard University, October 6-7, 2018.

In The News

Gallery

Homeland Images

Winter Count

Winter Count

Winter counts are pictorial calendars or histories in which tribal records and events were recorded by Native Americans in North America.

1934

May 22

Henrietta Mann Was Born

Twenty Stands Woman/Standing Twenty Woman Henrietta Mann was born at 4:47am, May 22, 1934 at the Clinton Indian Hospital, Custer County, Oklahoma, the daughter of Holy Bird Henry Mann and Day Woman Lenora Wolftongue Mann, each 4/4 Cheyenne.

Paternal Grandparents: Spotted Horse Fred Mann and The Woman Who Comes to Offer Prayer/Prayer Woman/Prayer Cloth Woman Lucy Whitebear Mann

Maternal Grandparents: Deer Elmer Wolftongue and Bertha Powder Face Wolftongue

Paternal Great-Grandmother: Homa’oestaa’e/Homae’voestaa’e White Buffalo Woman was a Sand Creek and Washita Survivor. She is often referred to just as Voestaa’e, which translates as White Buffalo Calf Woman.

On the first morning following the coming home of mother and child, White Buffalo Woman blessed the infant Henrietta in the old way. She held her body as one holds a pipe, and pointed her headfirst to each of the four sacred directions of the universe (SE, SW, NW, NE), up, then laid her gently upon the earth supported by her hands. She was wrapped in a softly tanned calf hide, which was her primary blanket. Afterward, she prayed for the baby, and for all those assembled, who had come to welcome the infant to life on earth and to witness this special ceremony.

Henrietta selected Chairman of Christmas Celebration

As an infant of less than one year of age, Henrietta was selected by the Hammon Whiteshield Camp Christmas Committee to be the Chairman of their annual Christmas Celebration. As she was still but a baby, her parents, grandfather, and great-grandmother assumed this role on her behalf and carried out the celebration. It was looked upon a community honor and, essentially, became Henrietta’s first servant leadership role.

1938

White Buffalo Woman walked away from this Earth

White Buffalo Woman walked away from this earth to go to live in that eternal camp in the stars. She lies at rest in the Hammon Indian Mennonite Cemetery, Hammon, OK far from the place she was born in what is believed to be Wyoming Territory in 1853. She was among the last of the Cheyenne to make the break from the Buffalo and Horse Culture to life on the Southern Plains.

But two generations removed from Cheyenne Horse Culture, the Mann family still kept a herd of horses. A beautiful black and white paint was born and given to Henrietta, whom she named Ginger. Until the day they walked away from earth, the two men were always proud to proclaim that Henrietta had broken the pony herself, as was oftentimes the case for Cheyenne women.

Henrietta grew up primarily in a Cheyenne speaking environment, and even after she was enrolled in public school, one of her aunts Ruth Sooktis-Mann Big Left Hand moved in with the family. Ruth became her private Cheyenne language teacher every evening after she came home from school. Dinner conversation was in Cheyenne, but afterward, the language became bilingual, acknowledging the fact that she had to also improve her English speaking skills.

1950s

Selected to be part of Cheyenne dance group

Early in the 1950s during summer breaks, Henrietta was among those selected to be a part of the Cheyenne dance group who participated in dance exhibitions at the Gallup Intertribal Ceremonial, Gallup, NM for which Albert Hoffman was the Director. She was also selected as a member of the dance group which danced at Fourth of July gatherings in Flagstaff, AZ for which David Fan Man was the Director.

1951

Graduated from Hammon High School

Graduated from Hammon High School, Hammon, Oklahoma as the Salutatorian of her graduating class.

Upon high school graduation, Henrietta’s parents and grandfather put up a Native American Church, peyote meeting for her, the last time they did so. Her mother brought in the morning water. They did so to give thanks for her having acquired a high school diploma and to ask for continued guidance in her pursuit of higher education, as she was going on to college that summer.

Many years later in 1982 after she had completed her Doctor of Philosophy degree, Joe Antelope and her father, who had both attended her high school graduation peyote meeting were discussing the completion of her university education and agreed that Ma’heo’o, the Cheyenne “Great One” had heard their prayers.

Mr. Antelope had been the Fireman at that 1951 peyote meeting, and he later became the Keeper of the Cheyenne Sacred Arrows, the highest spiritual authority among the Cheyenne.

1954

Graduated from Southwestern State College

Graduated from Southwestern State College, Weatherford, Oklahoma with a Bachelor of Arts Degree in Education with a major in English (July 29).

In acknowledgment of this educational achievement, the family changed her Cheyenne name to that of her paternal grandmother, Ho’e-osta-oo-nah’e, which translates into English as The Woman Who Comes to Offer Prayer/Prayer Woman/Prayer Cloth Woman.

1955

April 21

Mark Alan Thompson born

Mark Alan Thompson, son born April 21, 1956, from Henrietta’s first marriage to George Lewis Thompson. Mark died September 12, 1990, from renal failure and hypotension exacerbated by chronic alcoholism. It is the most heartbreaking experience to lose a child.

1959

Married Alfred Whiteman, Jr.

Married Alfred Whiteman, Jr. (Cheyenne-Arapaho) Commercial Artist/Indian Artist. Born in Colony, Oklahoma, his mother was Nellie Rouse also known as Emily Washee (Cheyenne); his father Alfred Sr. was the grandson of Southern Arapaho Chief Little Raven, who signed the 1861 Treaty of Fort Wise, the 1865 Treaty of the Little Arkansas, and the 1867 Treaty of Medicine Lodge.

Chief Little Raven’s daughter Anna attended Carlisle Indian Industrial Training School in Carlisle, PA. Upon her return home, she married White Shirt (Arapaho). Two of their children Stephen and Ruth were listed on the Cheyenne and Arapaho Tribal Rolls as White Shirt; however, their youngest son Alfred was listed on the Tribal Rolls with the last name of Whiteman. Technically he should have been Alfred Whiteshirt.

1960

October 25

Alden Alfred Whiteman was born

I had grown up as virtually an only child and did not have a younger brother until I was eleven years old. His name was Ame’haohtse Flying Man Henry Mann, Jr. and I loved, will always love, this one sibling of mine, who died in 1979. I treated him like a living doll and cared for him as an older “sister mama” does. He used to call me “Mama.”

It was not until I was an adult that I learned that my parents had invoked a seldom-used Cheyenne tradition and made a vow to not have another child for ten years. Few parents made such a vow, which if broken would result in the death of the child. Such a sacrifice was made to give the child the best upbringing possible and to provide a strong cultural foundation. I finally understood why I never had siblings, although I had always wanted them.

My first magnificent love was my great-grandmother White Buffalo Woman. My first best friend was my grandfather Fred Mann, who made his home with us.

My father’s three sisters lived with us until the oldest aunt Mariam married. She was named for her aunt in English and Cheyenne. She was also Crooked Nose Woman. The other two, Rubie, Flying Woman, and Lucille, Night Walking Woman went off to Chilocco Indian School in Arkansas City, KS.

My grandfather had attended Chilocco for a while. He and his friend Amos White Hawk just showed up at the Chilocco school gates one day. They informed the administrator that they wanted to go to school, but would leave when they decided.

At that time, the federal government required three years of consecutive mandatory attendance at Off-Reservation Boarding Schools.

Because I grew up virtually an only child, I wanted to have a large family. Thus, Al and I had three children:

October 25, 1960:

Alden Alfred Whiteman

Vaoseva = Deer; Nanose’hame = Mountain Lion

January 4, 1962:

Montoya Ann Whiteman

Ma’ohkeena’e = Red Feather/Tassel Woman

November 20, 1963

Jackie Ladean Whiteman

Ame’ha’e = Flying Woman

1962

January 4

Montoya Ann Whiteman born

January 4, 1962:

Montoya Ann Whiteman

Ma’ohkeena’e = Red Feather/Tassel Woman

The family moved from Oklahoma City to Stillwater, OK

The family moved from Oklahoma City to Stillwater, OK when Al got a job as a commercial artist in the Public Information at Oklahoma State University (OSU).

By this time my aunt June Wolftongue, my mother’s sister, was living with us. She helped me with my children, and we gave Montoya her “grandmother” June’s Cheyenne name Red Feather.

1963

November 20

Jackie Ladean Whiteman born

November 20, 1963

Jackie Ladean Whiteman

Ame’ha’e = Flying Woman

Enrolled in graduate school at OSU

Since I have a great love for education, my late husband and I decided that I should pursue work toward a Master’s Degree. I consequently enrolled in graduate school in the English Department at OSU on January 23, 1963.

By the end of that year, we had seven family members, and we were one big, happy family. We also realized the cost of providing for a large family, and I went to work as the secretary in the Department of Art at OSU, and attended graduate school part-time. I stayed in the Art Department until I completed my Master’s Degree in English, and left to assume a university position at Cal Berkeley in early 1970.

In the intervening years, I juggled work and family. We also spend much time vacationing and driving to western Oklahoma to visit family and to attend dances, pow wows, meetings, and ceremonies. The children loved spending time with family, especially their “cousins.” It was their time for cultural grounding, and the beauty was they all got to know my grandfather Spotted Horse Fred Mann.

1966-1967

Elected representative of the Cheyenne & Arapaho Business Committee

I was elected the Hammon District Representative to the 15th Council of the Cheyenne & Arapaho Business Committee, headquartered at Concho, Oklahoma for a two-year term. I became the first woman ever elected to represent the Hammon Cheyenne District on the Tribes’ Business Committee.

My late husband Alfred Whiteman, Jr. also was elected as the El Reno District Representative that term. We became the first husband and wife team to ever serve in this capacity to this day.

Lawrence Hart, former jet pilot, who was the Chairman of the Business Committee, appointed me as the Chair for the Cheyenne and Arapaho Scholarship Committee. It had its own budget and operated autonomously from the Business Committee.

When we as a Business Committee finally settled our land claims with the U.S. government, we created a $500,000 trust fund for education, established a minors’ trust fund, and distributed per capita payments of $2,325.00 to all adult tribal members. I testified before the United States House of Representative on the educational trust fund, and Chief Ben Whiteshield of my district, happily announced that I was going to “Washingdyne.”

1969-1970

Became President of the Advisory School Board to the Dept. of the Interior

In keeping with the federal policy shift to Indian Self-determination, school boards were created for BIA schools, which included the one at Concho. I subsequently became the President of the Advisory School Board to the Department of the Interior, Bureau of Indian Affairs, Concho School, Concho, Oklahoma. The Concho (Manual Labor) School was located on the former Cheyenne and Arapaho Reservation.

1970

Employed as Coordinator of Native American Studies at University of Berkeley

Employed as Lecturer/Assistant Coordinator, then Coordinator, Native American Studies, Department of Ethnic Studies, University of California, Berkeley (March 1970 -June 1972). Native American Studies was new to the college/university campuses of this nation and was in the initial stages of being integrated into college/university curricula.

I arrived in Berkeley after 78 Bay Area Native Americans had moved on to Alcatraz Island in the San Francisco Bay, 1.25 miles from San Francisco. While there, they issued a “Proclamation to the Great White Father and All His People,” stating they re-claimed the island by right of discovery and offered a treaty of perpetuity, “for as long as the sun shall rise and the rivers go down to the sea.” They further observed that Alcatraz resembled most Indian Reservations in that it has no fresh running water; inadequate sanitation facilities; high unemployment; and no health care or educational facilities. Furthermore, they wanted the ships that entered the Golden Gate to see Indian land first.

In a separate letter dated December 16, 1969, they invited delegates from every Indian nation to join them. There they wished to establish a Cultural Center, a college, a religious and spiritual center, a museum, a center of ecology, and a training school.

Most of the Native American students who were attending UC Berkeley’s Native American Studies Program were on “The Rock” instead of on-campus attending classes. I had to go out to Alcatraz to meet my student-activists, most of whom eventually returned to school. It was strange to be teaching in Native American Studies and to not have any Native American students.

May 24

Graduated from Oklahoma State University

Graduated from Oklahoma State University, Stillwater with a Master of Arts Degree in English (May 24). I had completed my degree the previous Fall Semester but it was not conferred until the spring commencement, and I was already employed in my first university teaching position.

1972

Accepted tenure track position at the University of Montana

I did not enjoy city living and applied for two positions in Native American Studies at Western Washington University, Bellingham, and the University of Montana, Missoula. I was offered a tenure track position at both and chose the University of Montana.

Appointed Director/Assistant Professor, American Indian Studies, University of Montana

Appointed Director/Assistant Professor, American Indian Studies, University of Montana, Missoula (August). The University eventually changed the name to Native American Studies.

During my first semester of teaching and administrator of American Indian Studies (AIS) at UM, the contingent of the Trail of Broken Treaties, which originated in Seattle came to the University and asked the Kyi Yo Indian Club to assist them with lodging, meals, equipment, and supplies. Next thing I knew, Russell Means invited our Indian students to join the Trail of Broken Treaties and accompany other activists of the American Indian Movement to Washington, D.C.

The Dean of Arts and Sciences, in which AIS was located, agreed to let the fifteen students who wished to join the caravan go, and to also earn fifteen hours of Omnibus credit, provided they did their assigned academic work which consisted of a two-part journal:

- What actually happened, and

- How I felt about it.

He also appointed two other professors to assist me with logistics and evaluation of the journals when they returned.

Transportation was a critical issue and the students raised enough money in several days to purchase three cars. Off they went. The caravans, which had taken different routes simultaneously reached Washington D.C. and when communications with the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) broke down, the activists occupied the BIA building.

This caused me endless concern, but fourteen students and journals eventually returned. On their way back home, the fifteenth student decided to just go home to Wisconsin. We were all so glad to see them return and we had a welcome home feed for them.

We invited John Woodenlegs, Chairman of the Northern Cheyenne Nation to come to deliver a welcome back home speech to the students, and he told them the following:

“Before Custer left the east to take care of the Indian problem out west, the government asked him to return to Washington D.C. and report his findings so they would know how deal with these Indians.” Furthermore, they said “they would do nothing until he came back.”

He added: “We know what happened at the Little Big Horn, and I hope while you were in Washington D.C. you took the time to tell the government that ‘Custer won’t be back. Now they can do something about us Indians!”

We, three professors, decided the students’ journals were so exceptional that we would attempt to have them printed into a book, which we would title Tell Them Custer Won’t be Back based upon Mr. Woodenlegs’ commentary. The Indian Historical Press of San Francisco agreed to publish the book, but when the contract arrived, there were too many liabilities for the students, and we dropped the book idea. The journals are now in the custody of the University of Montana Library.

So much for my first semester at the University of Montana, almost my last, as well. The university had liked the Indian activism I brought to UM.

News Article

1976-1977

Included in Notable Americans of 1976-77

Included in Notable Americans of 1976-77, Raleigh, NC: American Biographical Institute.

1977

Became Interim Director & Lecturer at Harvard University

Took leave from UM to become the Interim Director and Lecturer, American Indian Program, Graduate School of Education, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA (January-June).

July

Promoted to Associate Professor, UM, Missoula

Promoted to Associate Professor, University of Montana, Missoula

1977-1978

Included in “Who’s Who of American Women“

Included in Marquis Who’s Who, Inc., Who’s Who of American Women, Chicago, IL: Marquis, Who’s Who, Inc., 1977-1978.

1978

Included in “The World Who’s Who of American Women in Education“

Included in The World Who’s Who of Women in Education, Cambridge, England, and New York, NY: International Biographical Centre, 1978.

Included in “The World Who’s Who of Women“

Included in The World Who’s Who of Women, Cambridge, England: International Biographical Centre, 1978.

1979

Attended Post-Graduate School at the University of New Mexico, Albuquerque

Granted a three-year leave without pay from the University of Montana, Missoula to attend Post-graduate School at the University of New Mexico, Albuquerque to work toward a doctorate degree (August 1979-June 1982).

Included in the Dictionary of International Biography

Included in the Dictionary of International Biography, Volume XV, Cambridge, England: International Biographical Centre, 1979.

Recipient Danforth Foundation Fellowship

1979-1980 Recipient Danforth Foundation Fellowship, Danforth Foundation, Saint Louis, Missouri. The Fellowship renewed annually in 1980-1981 and in 1981-1982 for study toward a doctorate degree at UNM, Albuquerque.

1980

Alfred Whiteman, Jr. Passed Away

Alfred Whiteman, Jr. passed away at the United States Veterans Hospital, Albuquerque, NM (December 5), after having fought diabetes for many years. The disease eventually resulted in renal failure, necessitating that he go on a dialysis machine, which was installed in our home in Missoula, in our apartment while I was teaching at Harvard, and in our home in Albuquerque. We put him on the dialysis machine at home for five years, but he ultimately died of cardiac arrest.

Death of the men in my family: grandfather, brother, son, and now a husband left sorrow in my heart that time has slightly diminished, but there is an emptiness left by my first friend, baby brother, firstborn, and my beloved husband.

1982

Graduated From The University of New Mexico, Albuquerque

Henrietta Whiteman graduated from the University of New Mexico, Albuquerque with a Doctor of Philosophy Degree in American Studies (May 16).

Title of Doctoral Dissertation: “Cheyenne-Arapaho Education, 1871-1982. It was written under Professor Richard E. Ellis, and later published into a book in 1997.

July

Promoted to Full Professor, UM, Missoula.

Promoted to Full Professor, University of Montana, Missoula.

Named Cheyenne Indian of the Year

Named Cheyenne Indian of the Year, for achievements in education, at the American Indian Exposition, Anadarko, Oklahoma.

1986

Federal Appointment as the Deputy to the Assistant Secretary/Director – Indian Affairs

1986-1987 Granted leave from UM on an Intergovernmental Personnel Assignment (IPA) to assume a federal appointment as the Deputy to the Assistant Secretary/Director – Indian Affairs (Indian Education Programs), Bureau of Indian Affairs, U.S. Department of the Interior, Washington, D.C. I became the highest-ranking woman in Indian Education in the federal government. Testimony at BIA Education Budget Hearings on The Hill was intimidating.

One of the most memorable events of my year in Washington, D.C. as the Director of Office of Indian Education Programs was the trip my Anadarko Area Office Line Officer, Dr. Carolyn Elgin and I made to the Sac & Fox community located in Nacimiento, Mexico. At their request, the parents and tribal leaders were concerned about having to withdraw their children from school while they followed the fruit harvest in the United States. They wanted to keep the family intact. They were interested in the possibility of having the BIA-OIEP purchase and equip a large bus as a travelling school. I liked the idea, especially about keeping the family together but the BIA was not receptive to this idea. Ultimately the children’s education suffered and their families were separated as parent(s) followed the seasonal harvest.

September 1

Attended The First Feast Held In Honor Of Oakerhater At The Washington National Cathedral

My aunt June Wolftongue and I attended the first feast held in honor of Oakerhater at the Washington National Cathedral in Washington, D.C. on September 1, 1986. The Episcopal Church had designated him as a Saint in 1985, making him the first Native American and Oklahoman to become a Saint in the Episcopal Church. On that feast day, my aunt and I carried the Christian elements for communion to the altar, and afterward joined other family members and the Oklahoma delegation for the service, parts of which were spoken in the Cheyenne language by Chief Lawrence Hart, an ordained minister.