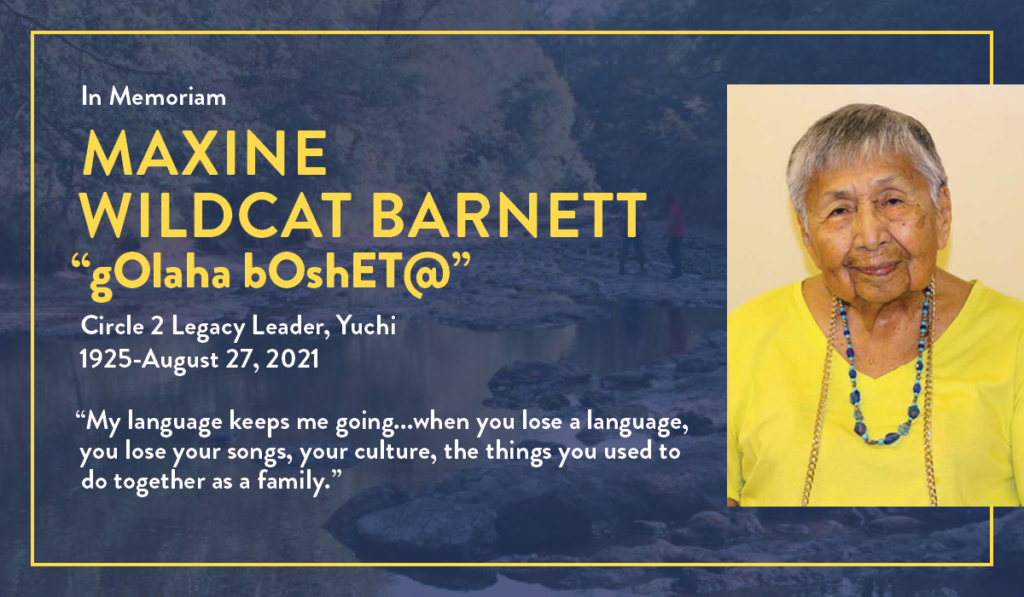

We celebrate the life of gOlaha bOshET (Maxine Wildcat Barnett) as she is surrounded by the love of her community.

Maxine’s goal was to ensure the Yuchi language was passed to the next generations. She effectuated her legacy using the Spirit Aligned Leadership Program to sustain and support her efforts. For some time, she was the last fluent Yuchi speaker – before she passed, she accomplished her goal in transferring the language to Yuchi youth.

We thank Grandmother Wildcat for her beautiful and important legacy. Engage with the enduring legacy of gOlaha bOshET, visit spiritaligned.org and support the Yuchi Language Project (tag).

Below are unpublished writings by the late Maxine Wildcat Barnett. In this, she shares what it means to carry on her language and what her homelands mean to her.

Maxine Wildcat Barnett on the Yuchi Language

Neither of my grandmothers could talk English. All they knew was Yuchi language. My parents too, only spoke Yuchi in our home. But when I was about seven years old we went to live with gOlaha (my grandmother), Eliza Pickett, f’alOKw@nE was her Yuchi name. She was the one who used to tell us many lessons through stories. I often thought, “How did she know so much?” She couldn’t read or write and she never went to school but she had so much wisdom that she had heard from her elders.

We didn’t have electricity or radio, so when gOlaha told us these old stories that was our education that was our learning about what it meant to beYuchi. She gave us medicine and taught us how to be Yuchi. I remember that she only told the dA’ElA (old stories) in the winter months so that is when I pass them on to the young people. My grandmother spoke the female form of the language. Men and women speak differently in Yuchi and it was important for me to learn to speak from her so that I could carry that on. Today, I am the last native speaker. I never thought things would turn out this way but here I am. I am the last connection from my grandmother to the young people today. I meditate on these old traditional stories and use those principles she taught me as I try to be a leader today.

I have had to reclaim my language and it has been a personal healing journey. When we were sent away to Chilocco boarding school we were separated and I wasn’t allowed to talk to the other Yuchis. So, eventually I lost my language. Well, that is, I always understood it, but I got to where I couldn’t put my sentences together anymore. I felt ashamed and like I had lost a part of myself when I returned home and couldn’t speak. I had to work to regain fluency in my language for many months over a few years. It was such a blessing to get where I could converse with the other elders in the Yuchi language. We shared stories and laughed. I could always sing in my language but now that I am able to pray in my language again, I feel much closer to the Creator. As my cousin, who also grew up with Grandma, used to say, we are the only ones given this language. It is as a gift from the Creator that has been entrusted to us. Now it’s up to us to carry it on.

Maxine Wildcat Barnett on Homeland

I attribute my long life to living off the land. I am 93 now and I grew up eating foods like zOt’E (wild onions), sumbE (wild mushrooms), shAd@bEnA (possum grapes), shw@ (poke salad), and other wild greens. We also raised our own food. We dried corn and pounded it using a corn pounder. We only went to town once a month. I still make zOshE (corn drink) and I teach the children in Yuchi classes how to make traditional foods.

Our grandmother was a medicine woman and all of our medicines came from the land like zOchathla (red root). As we make our language strong again, I believe the medicines will come back to heal us. Our sacred homeland was way over in what is today Georgia before the Trail of Tears. The coals from those original sacred ceremonial grounds were brought here to rekindle our ceremonial fires in these new lands.

I did not know my grandfathers. They left with the other men to fight against land allotment that was forced on our people. We almost forgot the word for ‘buffalo’ because they had been wiped out from our land for so long. But we still have a buffalo dance in our ceremonies. We still have a lizard dance that goes back thousands of years. In Yuchi, we do not have a word for “animals.” We do not think of humans as above “animals” because in our language they are just like us. In our language, we don’t have a way to say that we “own” animals. On the contrary, we say, p’aTA awAdOt’@, meaning simply that, “I placed a horse there. “When we speak in Yuchi about something, we automatically give its relation to the earth. In Yuchi, you can’t just say “There it is.” You must say whether “it” is standing, sitting, or lying in relation to the earth. So I must always pay attention to the way things are connected to the land. This is also the way we talk about people. Keeping our language alive is how we understand our unique relationship to the earth.